Machine Learning for Generative Art Without the Hype

Machine learning does sophisticated pattern matching and statistical generation, not magic. Understanding when it's actually useful versus when simpler approaches work better cuts through hype and enables critical use as artistic tool.

You've seen AI-generated images flooding social media. You've heard artists panic about being replaced. You've read breathless articles about how machine learning is revolutionizing creativity. But you're trying to figure out whether any of this actually serves artistic practice beyond generating novel images, whether there's substance beneath the hype, and what machine learning can genuinely do that other generative methods can't.

The answer is complicated. Machine learning offers specific capabilities that enable certain approaches to generative art, but it's not magic and it's not going to replace human artistic judgment. It's a tool, like any other computational approach, with particular strengths and significant limitations. Understanding what it actually does, when it's useful versus when simpler methods work better, and how to use it without becoming a tech demo requires cutting through marketing language and hype cycles.

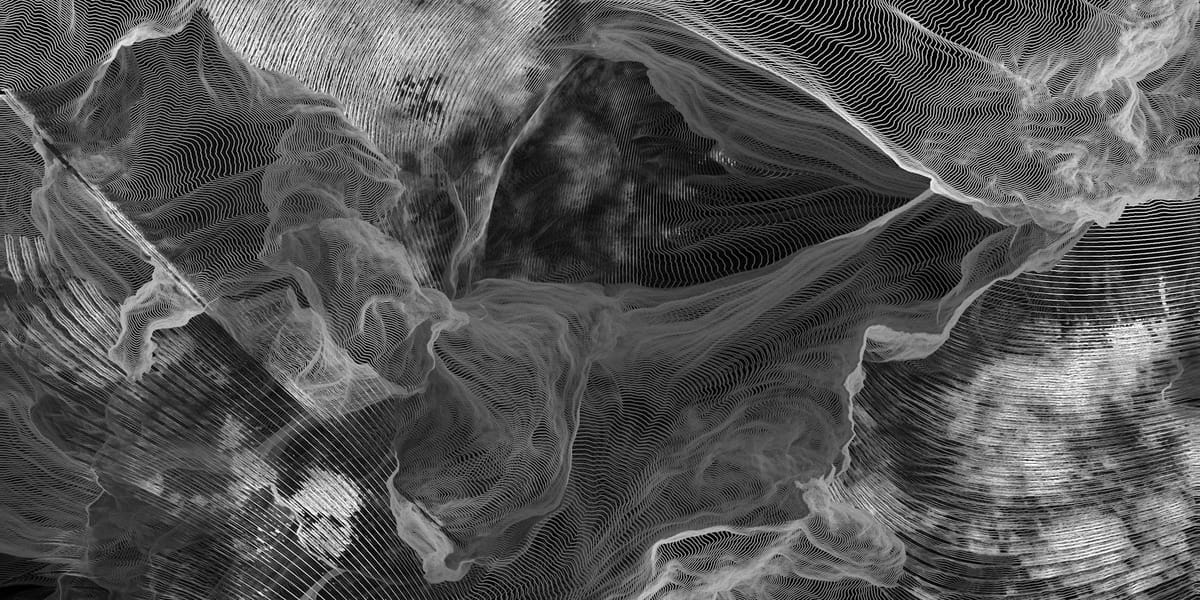

Machine learning for generative art means using algorithms that learn patterns from data and generate new outputs based on those learned patterns. This is fundamentally different from rule-based generative systems where you explicitly program every behavior. ML systems extract patterns from examples, which enables approaches that would be impossibly complex to program manually but also introduces unpredictability and requires different thinking about control and authorship.

Most artists don't need to understand the mathematics of neural networks or write ML code from scratch. But understanding conceptually what these tools do, when they're appropriate, and how to work with them critically rather than just applying them because they're trendy transforms ML from gimmick into potentially useful tool.

What Machine Learning Actually Does

Machine learning finds patterns in data through statistical methods and uses those patterns to make predictions or generate new outputs.

Unlike traditional programming where you write explicit rules telling the computer exactly what to do, machine learning provides examples and the algorithm finds patterns. You give it thousands of images and it learns what features make an image look like your dataset. You give it text and it learns statistical relationships between words.

This learning from examples is powerful when patterns are too complex to articulate as explicit rules. You can't easily write rules for "what makes an image look like a Rembrandt painting," but you can show an ML system hundreds of Rembrandt paintings and it will extract statistical patterns.

The algorithms don't understand anything conceptually. They're doing sophisticated pattern matching and statistical correlation. When a system generates text that seems meaningful, it's predicting likely next words based on statistical patterns, not understanding meaning. This distinction matters for setting realistic expectations.

Training requires large datasets. To learn patterns, ML systems need many examples—hundreds, thousands, sometimes millions depending on the task. For some artistic applications, getting adequate training data is straightforward. For others, it's prohibitive.

The trained model is essentially compressed representation of patterns found in training data. When you use it to generate new work, you're sampling from that learned pattern space. The outputs will resemble the training data in structural and statistical ways even when individual outputs are novel.

Generative adversarial networks (GANs), diffusion models, transformers, variational autoencoders, all are different architectural approaches to learning and generating. Each has different characteristics, strengths, and limitations. You don't need to understand the technical details, but knowing they're different tools for different jobs helps.

The generated outputs require curation. ML systems produce many outputs, most of which won't be interesting or useful. Artistic judgment in selecting, editing, and contextualizing generated material is where human creativity enters. The system generates possibilities; you decide what matters.

This curation role is legitimate artistic practice, though it differs from traditional making. You're working more like editor or curator than painter or sculptor, but the aesthetic and conceptual decisions still require judgment and expertise.

When ML Actually Adds Value Versus Simpler Approaches

Machine learning is not always the best tool for generative work. Understanding when it offers advantages over simpler methods prevents using complex tools unnecessarily.

ML helps when patterns are complex and hard to articulate explicitly. If you can write clear rules for what you want, traditional procedural generation is simpler and more controllable. Use ML when the pattern is too complex for explicit rules.

Example: Generating realistic human faces requires understanding complex patterns of facial structure, skin texture, lighting, that would be nearly impossible to program manually. ML trained on face images learns these patterns. This is good use case.

Counterexample: Generating geometric patterns or abstract forms based on mathematical relationships is better done with traditional procedural methods. The rules are clear and explicit. ML adds unnecessary complexity.

ML helps when you want to work with style transfer or learned aesthetic patterns. If you want to apply the statistical visual patterns of one dataset to another, ML methods like style transfer enable this. Traditional methods can't learn and apply complex stylistic patterns.

Traditional methods help when you want precise control. If you need to specify exact behaviors, explicit programming gives you that control. ML systems are probabilistic and don't guarantee specific outcomes. The trade-off is control versus learned complexity.

ML helps when generating variations within learned distribution. If you want endless variations that all share family resemblance to training data, ML generates novel instances from learned pattern space. This is different from random variation in programmed rules.

Traditional methods help when you understand the generative process intellectually and want to encode that understanding. Building explicit systems codifies knowledge. ML systems are often opaque—you don't know exactly what patterns they learned.

ML helps when training data is available and patterns you want exist in that data. If you can gather examples of what you want and the pattern exists in those examples, ML can extract it. Without good training data, ML fails.

ML costs more computationally than simple procedural generation. Training models requires significant computing resources, often GPU access. Running trained models also requires more computing than simple algorithms. Consider whether the benefit justifies the cost.

Cloud services like RunPod, Google Colab, or AWS provide GPU access without buying hardware, but they cost money for extended use. For serious ML work, expect to spend money on computing resources.

Working With Pre-Trained Models Versus Training Your Own

Most artists working with ML use pre-trained models rather than training from scratch, which makes ML accessible without massive datasets or computing resources.

Pre-trained models like Stable Diffusion, DALL-E, Midjourney, and others have learned patterns from millions of images. You can use these models through prompts without training anything yourself. This is the lowest barrier to entry.

Prompting is skill distinct from training. Writing effective prompts that generate desired outputs requires understanding how models interpret language and experimentation to find what works. Prompt engineering has become its own practice area.

Good prompting is specific about visual qualities, style references, composition, lighting, without overspecifying so narrowly that the model has no space to generate interesting variations. Finding this balance takes practice.

The limitation of pure prompting is you're working within the model's learned space. You can't make it generate things too far from its training data. It has biases and limitations baked in from training. Understanding these constraints prevents frustration.

Fine-tuning pre-trained models on your own smaller dataset adapts the model to your specific needs while requiring far less data and computing than training from scratch. You're adjusting existing knowledge rather than learning from zero.

Fine-tuning requires some technical knowledge but is increasingly accessible through tools like DreamBooth, LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation), and platforms that simplify the process. You need dozens to hundreds of examples rather than millions.

Use cases for fine-tuning include training on your own visual style, learning specific subjects or objects the base model doesn't handle well, or adapting to specific aesthetic domains not well represented in general training data.

Training from scratch requires massive datasets, expensive computing, and technical expertise. This is generally not practical for individual artists unless you have significant resources and technical background or collaborate with ML researchers.

Some artists do train custom models for specific projects, but it's substantial undertaking. The benefit is complete control over training data and model architecture, but the cost is high in time, money, and technical complexity.

Understanding Bias and What Models Actually Learn

ML models learn everything in their training data, including biases, cultural assumptions, and problematic patterns. Using ML critically requires understanding this.

Image generation models trained on internet images learn internet image culture, which includes biases about gender, race, aesthetics, representation. These biases appear in generated outputs whether you intend them or not.

Example: Asking for "CEO" might generate predominantly images of white men because training data reflected that bias. The model learned existing patterns including discriminatory ones. Being aware of this prevents mindlessly reproducing bias.

Dataset composition determines what model can generate. If training data lacks diversity, generated outputs lack diversity. If training data overrepresents certain aesthetics or subjects, generations will too. Understanding training data helps understand model capabilities and limitations.

Most commercial models don't fully disclose training data, making it hard to know exactly what biases exist. But being critical about outputs, questioning what patterns model learned and whether those patterns are ones you want to work with, is essential.

Some artists use ML systems to critique or expose these biases, generating outputs that reveal what models learned and questioning whether those learned patterns should exist. This critical use of ML is very different from uncritical application.

Copyright and training data ethics are contested territory. Models trained on copyrighted images without permission raise legal and ethical questions about whether that constitutes fair use or theft. Different jurisdictions are still determining legal frameworks.

Artists have legitimate concerns about their work being in training data without consent or compensation. Using ML generated imagery that learned from unconsented training raises ethical questions you should consider.

Some artists refuse to use systems trained on scraped data without artist consent. Others see it as transformative use comparable to learning from looking at other artists' work. This remains contested and you'll need to decide your position.

New models trained on licensed, consented, or public domain data are emerging in response to these concerns. Using these models addresses some ethical issues though they may have different capabilities due to different training data.

Practical Workflows for Artists

How you actually integrate ML into artistic practice determines whether it becomes useful tool or just generates images you don't know what to do with.

Starting with concept rather than generation prevents making work that's just "ML-generated stuff" without artistic purpose. What do you want to explore? What questions do you have? How might ML serve those goals?

If your concept is genuinely served by ML's capabilities—learning complex patterns, generating variations, style transfer, working with learned distributions—then ML is appropriate. If you're just using it because it's trendy, reconsider.

Iteration and curation are where artistic decisions happen. Generate many outputs, select the interesting ones, iterate on what works, reject what doesn't. This editorial process is artistic labor, not just passive consumption of generated images.

Some artists generate hundreds or thousands of images to find a few worth using. The curation is the work. This is similar to photographers shooting dozens of frames to get one good shot. The generating is exploration; the selecting is creation.

Combining ML with other processes integrates it into broader practice rather than making it the entire practice. Use ML-generated elements as source material for painting, collage, or further manipulation. Mix ML approaches with traditional making.

Anna Ridler's datasets and ML-generated imagery get combined with traditional drawing and painting. The ML is one tool among many, not the entire practice. This integration prevents work being solely about the technology.

Post-processing and editing generated outputs customizes them beyond what the model produces. Photo editing, digital manipulation, traditional techniques applied to prints, all make generated material your own rather than just model output.

The less the final work looks like raw model output, the more you've made it yours. If viewers can immediately identify it as Midjourney or Stable Diffusion output, you've probably not processed it enough.

Building datasets intentionally for training or fine-tuning gives you more control over what the model learns. Curating training data is curatorial and conceptual practice. What you include and exclude shapes what the model can generate.

Some artists create datasets as artworks in themselves. The training data isn't just functional but conceptually significant. The generated outputs emerge from that curated knowledge.

Documenting process including prompts, training data, model parameters, iterations, creates transparency about how work was made and preserves knowledge for future projects or for others interested in your methods.

This documentation also helps you understand what works and what doesn't, building knowledge across projects rather than starting from zero each time.

Critical and Conceptual Uses Beyond Pretty Pictures

The most interesting artistic uses of ML engage it critically or conceptually rather than just using it to generate images.

Exposing what models learned reveals biases, cultural assumptions, or patterns in training data. Artists generate outputs that make visible what the model absorbed, critiquing the training data or the technology itself.

Trevor Paglen's work examines what computer vision systems see and how they classify, exposing the biases and assumptions in ML systems. The work is about the technology's perspective, not just using technology as tool.

Working with training data as conceptual material makes the dataset itself artistic content. Kate Crawford and Trevor Paglen's ImageNet Roulette exposed how ImageNet training data classified people, critiquing both the dataset and systems trained on it.

Creating custom datasets of specific subjects or collecting unusual training data generates models with particular biases or capabilities. The curation of training data becomes conceptual practice determining what the model can make.

Adversarial approaches that break or confuse ML systems explore their limitations and failures. Making images that fool classifiers, generating outputs that reveal model biases, or creating inputs that produce unexpected outputs all engage technology critically.

These adversarial approaches are often more interesting than straightforward use because they reveal how systems actually work, what they get wrong, where they fail, questioning the technology's authority.

Collaboration between humans and ML where outputs require human intervention, editing, or decision-making positions technology as collaborator with its own agency and limitations rather than tool that executes human will perfectly.

This collaborative framing acknowledges that ML outputs aren't fully under your control, that the system has its own statistical "understanding" that differs from yours, and that working with it means negotiation.

Using ML to generate source material for traditional techniques brings together computational and manual processes. Print ML-generated images and paint over them, use generated forms as templates for sculpture, incorporate ML elements into installation.

This integration creates work that couldn't exist without ML but isn't purely computational, bridging digital and physical, automated and handmade.

Systematic exploration of parameter spaces or prompt variations creates bodies of work investigating how changing inputs affects outputs. This systematic approach can reveal patterns in how the model works.

Variations on single prompt or parameter sweeps generate series showing gradual change across generation space, making visible the model's latent space or how it responds to different conditions.

Technical Basics You Need to Know

You don't need to understand the mathematics of neural networks, but some basic technical knowledge helps you work more effectively.

GPU versus CPU: Graphics processing units (GPUs) are much faster than central processing units (CPUs) for ML work. Training and running ML models on GPU is often 10-100 times faster than CPU. Access to GPU matters for practical use.

Consumer GPUs like NVIDIA RTX series can run smaller models locally. Larger models require professional GPUs or cloud services. Knowing your hardware capabilities determines what you can do locally versus what requires cloud resources.

Model size and requirements: Models have different computational requirements. Smaller models run on modest hardware. Larger models require powerful GPUs and lots of memory. Understanding model requirements prevents trying to run models your hardware can't handle.

Cloud platforms like Google Colab offer free limited GPU access, enough for experimentation. Paid services like RunPod, Lambda Labs, or AWS provide powerful GPUs on-demand. Costs range from dollars per hour to hundreds depending on GPU type.

Local versus cloud: Running models locally gives you control and privacy but requires appropriate hardware. Cloud services provide access to powerful resources but cost money and require internet connection. Most serious work involves both.

Open source versus commercial APIs: Open source models like Stable Diffusion can be run locally or on your own cloud instances, giving you control. Commercial APIs like DALL-E or Midjourney are easier to use but give you less control and may have usage restrictions.

Open source advantages: Control over model, no usage restrictions, can fine-tune, can examine how it works. Disadvantages: Requires more technical knowledge, need to handle infrastructure.

Commercial API advantages: Easy to use, no infrastructure management, often higher quality results. Disadvantages: Cost per generation, usage restrictions, less control, outputs may belong to platform.

Basic Python knowledge helps for working with open source models and tools. You don't need to be programmer but understanding basic syntax, running scripts, installing packages makes many ML tools accessible.

Many tutorials and communities exist for artists using ML. Resources like Hugging Face, Reddit's r/StableDiffusion, GitHub repositories, and YouTube tutorials provide support for learning.

When to Collaborate With Technical People

Many successful art projects using ML involve collaboration between artists and people with technical expertise. Understanding when to collaborate versus when to learn yourself helps you approach ML practically.

Complex technical requirements beyond basic model use often benefit from collaboration. If you want custom model architecture, novel training approaches, or integration with other systems, working with ML engineers or researchers provides expertise.

Artists often have conceptual vision but lack technical skills to implement it. Developers have technical skills but may lack artistic vision. Collaboration brings together complementary capabilities.

Establishing clear roles prevents confusion. Artist maintains creative direction and conceptual vision. Technical collaborator handles implementation, explains what's possible and what's not, suggests technical approaches.

Communication between artists and developers requires translating between aesthetic and technical languages. Learning enough about each other's domains to communicate effectively is essential for successful collaboration.

Artists need to explain what they want aesthetically and conceptually in ways developers can understand technically. Developers need to explain technical possibilities and limitations in ways artists can understand without extensive technical background.

Finding technical collaborators: University research labs often have students or researchers interested in artistic applications. Hackathons and creative coding communities connect artists and developers. Online platforms like GitHub or ML communities can help find collaborators.

Be clear about expectations, credit, compensation from the start. Collaborative agreements prevent later conflicts about who did what, who gets credit, who owns outputs.

Some institutions have artist-in-residence programs specifically for computational or ML work, providing both technical support and resources. These residencies can be excellent opportunities to explore ML with expert support.

Avoiding the Hype Cycle

ML in art is subject to intense hype cycles that obscure practical realities. Maintaining critical distance helps you use technology effectively without getting swept up in marketing.

AI art generators are tools, not magic. They do sophisticated pattern matching and statistical generation, but they're not conscious, don't understand meaning, and don't have taste or artistic judgment. Anthropomorphizing them obscures how they actually work.

Claims that ML will replace artists are marketing hype, not reality. Technology changes how artists work but doesn't eliminate need for artistic vision, curation, conceptual thinking, cultural understanding, judgment about what matters.

The technology itself is neutral. What matters is how you use it, what you make, what concepts you explore. A tool being new doesn't make work using it automatically interesting or valuable.

Fashion cycles in art world mean ML-generated work gets hyped currently but this will fade like any trend. Making work because it's trendy guarantees it becomes dated when trends shift. Make work because the approach serves your concepts.

Technical capabilities improve rapidly, meaning today's cutting-edge model is next year's obsolete baseline. Don't center work on specific tool's current capabilities since they'll be surpassed. Center work on concepts and questions that remain relevant as technology evolves.

Marketing language from tech companies obscures limitations and overstates capabilities. Read critically, understand that companies selling technology have incentive to hype it, and maintain healthy skepticism about claims.

Many technical limitations exist that promotional materials don't emphasize: bias in training data, computational costs, environmental impact of training large models, copyright issues, difficulty controlling outputs precisely, tendency toward generic outputs.

The most interesting work using ML often engages it critically, questions it, reveals its limitations, rather than accepting it uncritically as revolutionary breakthrough. Critical engagement produces more substantial work than enthusiastic adoption.

Environmental and Ethical Considerations

ML has environmental and ethical costs that responsible use requires acknowledging and considering.

Training large models requires enormous energy consumption and produces significant carbon emissions. GPT-3 scale models used electricity equivalent to hundreds of cars running for years. This environmental cost is real even though it's invisible to users.

Using pre-trained models rather than training from scratch reduces your environmental impact since training cost is amortized across many users, but it doesn't eliminate it. Inference (running models) also uses energy.

Some research focuses on making ML more efficient, reducing computational and environmental costs. Using smaller models when they're adequate, optimizing code, choosing efficient architectures all reduce impact.

Being conscious of environmental costs doesn't mean never using ML, but it means considering whether the artistic value justifies the resource use, and choosing efficient approaches when possible.

Copyright and labor issues around training data remain unresolved. Artists whose work trained models without consent have legitimate grievances. Using such models makes you complicit in that system.

Following developments in ethical AI, attending to debates about training data rights, considering whether you're comfortable using systems trained on scraped data, all are part of responsible practice.

Some organizations and initiatives work on ethical ML, consensual training data, fair compensation for data contributors. Supporting and using these systems when available helps push the field toward more ethical practices.

Automation and labor displacement concerns are real. ML systems that generate images quickly affect commercial illustrators and photographers. Being aware of these impacts and considering how your use of ML affects others' livelihoods matters.

This doesn't mean never using automation, but it means being thoughtful about context, considering alternatives, and recognizing that technology adoption has social consequences beyond individual practice.

Practical First Steps

If you want to experiment with ML for generative art, here's pragmatic advice for getting started without overwhelming yourself.

Start with accessible tools requiring minimal technical knowledge. Platforms like Midjourney, DALL-E, or Artbreeder let you experiment through web interfaces without coding or installing anything. Use these to understand what ML-generated imagery looks and feels like.

Experiment with prompting to understand how language affects generated outputs. Try different prompt structures, level of detail, style references, see what produces interesting versus generic results. This builds intuition about working with models.

When you're comfortable with basics, try tools with more control. RunwayML, Stable Diffusion interfaces, or Google Colab notebooks provide access to models you can adjust and fine-tune while remaining relatively accessible.

Learn basic prompt engineering and parameter adjustment. Understanding how sampling steps, guidance scale, seeds, and other parameters affect outputs gives you more control over generation process.

If you want to go deeper technically, learn basic Python and work through tutorials for Stable Diffusion or similar open source models. Many step-by-step guides exist for artists without extensive programming background.

Join communities of artists using ML. Reddit, Discord servers, forums, Twitter all have communities sharing techniques, troubleshooting, showing work. Learning from others accelerates your own learning.

Experiment with different models and approaches to find what serves your artistic interests. Diffusion models, GANs, transformers, each have different characteristics. Some might resonate with your practice more than others.

Document your experiments and what you learn. Notes about what worked, what didn't, interesting prompts or parameters, all create knowledge base you can reference and build on.

Start small with focused experiments rather than trying to make magnum opus immediately. Generate variations, test approaches, explore capabilities through modest experiments before committing to major projects.

Think about how ML might serve concepts or questions you already have rather than adopting it because it's new. Best use comes from it serving existing artistic concerns, not from forcing concerns to fit the technology.

Moving Beyond Generated Images

Most ML discussion focuses on image generation, but other applications exist that might be more interesting for your practice.

Sound and music generation using ML models trained on audio creates generative music, sound textures, or synthesized sounds. Models like Jukebox, MusicLM, or AudioLM generate audio from text or other inputs.

Artists working with sound can use ML for generating soundscapes, creating variations, transforming audio, or developing new synthesis approaches. This is less explored than image generation but equally viable.

Text generation models can create poetry, prose, scripts, or conceptual text-based work. Artists working with language can use ML to generate textual elements, collaborate with generative text, or critique language models.

Motion and animation using ML for interpolation, style transfer, or generating movement creates possibilities for video and animation work. Models can generate in-between frames, apply styles temporally, or create motion from static images.

Interactive systems that respond to viewer input using ML for classification, recognition, or generation enable responsive installations. Computer vision models can recognize gestures or objects, triggering generative responses.

Data visualization and ML pattern finding can reveal structure in large datasets. Using ML to find patterns in data then visualizing those patterns creates work about information, data culture, or algorithmic perception.

Combining modalities like generating images from sound, sound from text, text from images, all are possible with multimodal models. These cross-modal generations create unexpected relationships between different media.

Physical outputs from digital generation: Using ML to generate designs for 3D printing, CNC machining, textile patterns, ceramic forms, translates computational generation into physical objects and materials.

The Future Is Just More Options

ML adds capabilities to generative art practice but doesn't replace other approaches or eliminate need for artistic judgment and vision.

Artists have always used available technology from camera obscura to Photoshop. ML is another tool in a long history of technology adoption. Some artists will use it extensively, others not at all, both positions are legitimate.

The technology will continue developing rapidly. What's difficult now becomes easier. What's impossible now becomes possible. Staying aware of developments without feeling obligated to adopt everything helps you make informed choices.

Understanding fundamentals of how ML works conceptually serves you better than learning specific tools that will become obsolete. The concepts persist even as implementations change.

Critical engagement with ML produces more interesting work than uncritical enthusiasm. Questioning what models learn, how they work, what they get wrong, generates substantial artistic investigation beyond surface-level generation.

Combining ML with other generative approaches, traditional techniques, conceptual frameworks, creates hybrid practices richer than pure ML work. Integration matters more than isolation.

Your artistic vision and concepts drive good work. Technology is means to realize vision, not source of vision. If ML serves your concepts, use it. If other approaches work better, use those. The work matters more than the tools.

Machine learning for generative art offers specific capabilities that enable working with learned patterns, generating variations within pattern spaces, and creating outputs too complex to program explicitly. But it's not magic, doesn't replace artistic judgment, and isn't always the best approach. Understanding what it actually does, when it adds value versus when simpler methods work better, and how to use it critically rather than just following hype cycles transforms it from trendy gimmick into potentially useful tool in broader artistic practice. The technology serves the work; the work doesn't serve the technology.