How Pointillism Exploits Optical Mixing vs Pigment Mixing

The science behind pointillism's optical color mixing. Why Seurat's dots work at distance but fail up close, and what retinal mixing actually achieves versus theory.

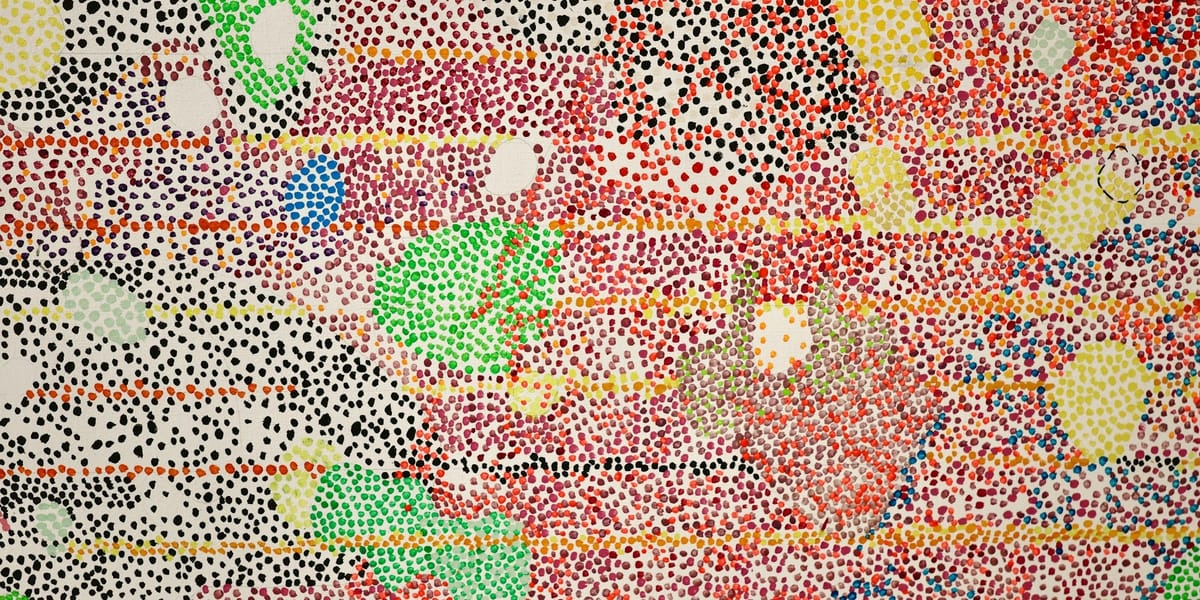

Pointillism promises something that sounds almost magical: pure colors placed side by side that mix in the viewer's eye rather than on the palette, creating luminous effects impossible through traditional pigment mixing. Georges Seurat and Paul Signac built entire painting careers on this principle, applying scientific color theory to create works that were supposed to demonstrate superior understanding of light and perception. The reality is more complicated and considerably less magical than the theory suggests.

The technique works, but not quite the way its inventors thought it did. Optical mixing does occur at appropriate viewing distances, but the mechanism isn't the clean additive color combination that Seurat imagined. Physical limitations of human vision, the actual reflectance properties of pigments, and the messiness of real-world viewing conditions all conspire to produce effects that diverge significantly from theoretical predictions. Understanding what's actually happening when you look at a pointillist painting requires sorting through what the artists believed, what the science of their era claimed, and what modern vision research has revealed about how we actually process this kind of visual information.

This isn't about dismissing pointillism as failed science. The paintings work as visual experiences, and the technique produces distinctive effects that matter aesthetically regardless of whether the underlying theory was correct. But understanding the gap between theory and reality helps explain both why pointillism creates the effects it does and why it never became the dominant painting technique its advocates thought it would.

The Theory Behind Optical Mixing

Seurat developed pointillism, which he called divisionism or chromoluminarism, based on color theories current in the 1880s. The core idea was that placing pure spectral colors in small dots next to each other would create color mixing through optical combination rather than physical pigment mixing. This was supposed to produce more luminous, vibrant results than mixing pigments on the palette, which inevitably creates duller colors through subtractive mixing.

The theoretical foundation came primarily from Michel Eugène Chevreul's law of simultaneous contrast, Ogden Rood's writings on color perception, and Charles Blanc's grammar of painting. These sources described how colors affect each other when placed in proximity, how the eye perceives complementary colors, and how light combines differently than pigments. Seurat synthesized these ideas into a systematic painting technique meant to harness optical phenomena for greater chromatic intensity.

The appeal was straightforward. When you mix blue and yellow pigment on a palette, you get green, but it's a relatively dull green because both pigments absorb portions of the spectrum, and mixing them combines these absorptions. But if you place tiny blue and yellow dots next to each other, the theory suggested they would mix optically to create a brighter green as the eye combines the separate color signals. This additive mixing should work more like mixing colored light beams than mixing physical pigments, producing more saturated results.

Seurat believed this technique aligned painting with scientific understanding of light and color perception. He saw traditional painting methods as empirical and crude, relying on trial and error rather than systematic application of optical principles. Pointillism was meant to be painting elevated to science, with predictable results based on understanding how vision actually works. The systematic application of small uniform dots across the entire canvas surface was part of this scientific approach, removing the arbitrary gestural marks of traditional brushwork.

The idea also connected to broader late nineteenth-century fascination with scientific rationalization of art. Just as photography had mechanized image-making and color theory had systematized palette choices, pointillism promised to bring systematic optical principles to the fundamental act of applying paint to canvas. It fit the positivist intellectual climate that saw science as the path to progress in all domains, including aesthetics.

But the theory contained assumptions about vision that weren't quite accurate. Seurat thought of the eye as performing a kind of averaging or blending of adjacent color stimuli at distance, creating new colors through this optical combination. The actual mechanisms of color vision are more complex and don't perform the clean additive mixing the theory required. This gap between theory and perceptual reality shapes what pointillist paintings actually do versus what they were intended to do.

What Actually Happens in Retinal Mixing

Optical mixing in pointillism doesn't work through additive color combination the way mixing colored light does. What actually happens involves spatial averaging of luminance and color signals that our visual system performs when resolving fine detail exceeds its capacity. This produces effects that somewhat resemble the theoretical predictions but through different mechanisms and with significant limitations.

When you view a pointillist painting from appropriate distance, individual dots become too small for your visual system to resolve separately. Your retina and visual cortex receive information about the colors present in a small area but can't distinguish the precise spatial arrangement. The visual system averages this information, producing a color perception based on the combined stimuli. This is spatial averaging, not true additive mixing, and the distinction matters.

The resolution limit of human vision is approximately one arc minute under good conditions, meaning details subtending less than this angle at the eye blur together. For a dot that's 2mm across, this means viewing distances beyond about seven meters before complete blending occurs. At intermediate distances, partial blending creates a different effect where individual dots remain somewhat visible while also contributing to an averaged color perception. The painting looks different at three meters versus ten meters versus twenty meters, shifting between visible pointillist structure and fully blended appearance.

The actual color that results from this spatial averaging depends on the proportion and arrangement of different colored dots within a given area. If you have equal areas of pure blue and pure yellow dots, the averaged perception won't be a bright green as additive mixing would produce. It will be closer to a desaturated olive or grayish tone because you're still dealing with pigment reflectance properties, just averaged across space rather than mixed on the palette. The subtractive nature of pigment color doesn't disappear just because the mixing happens in the eye rather than in the paint.

Luminance averaging works more predictably than hue averaging. If you alternate light and dark dots, they average to middle values at distance in fairly straightforward ways. This is why pointillist paintings often succeed at creating effective value structure and atmospheric effects even when the color mixing doesn't perform as theorized. The tonal scaffolding works regardless of whether the color theory delivers on its promises.

Simultaneous contrast effects do occur in pointillist works, but they're not the same as optical mixing. When you place complementary colors in small dots next to each other, they enhance each other's intensity through contrast effects. Orange dots look more orange next to blue dots and vice versa. This creates chromatic intensity, but it's a different phenomenon than the dots actually mixing to create new colors. Seurat conflated these separate optical phenomena, assuming that simultaneous contrast and optical mixing would work together to produce superior color effects.

The messiest part of actual optical mixing is that it's highly dependent on viewing conditions that vary enormously. Light intensity affects how colors appear. Viewing angle matters, especially with glossy paint surfaces. The background color surrounding the painting influences color perception through contrast effects. Individual viewer differences in color vision, visual acuity, and even pupil size all affect how pointillist works appear. What Seurat could control was the paint on the canvas. What happened in viewers' visual systems was far less predictable than the theory suggested.

Modern vision science has also revealed that color perception isn't a simple response to wavelength stimuli but involves complex neural processing that varies with context. The visual system doesn't just average color information in some mechanical way. It performs sophisticated analysis that takes into account spatial frequency, surrounding colors, learned expectations about objects and materials, and top-down cognitive influences. Trying to predict what color will be perceived from knowledge of the physical stimuli alone, which is what pointillist theory attempted, turns out to be fundamentally limited.

Why Pointillist Paintings Fail at Close Range

Walk up to a Seurat and the whole composition disintegrates into a field of colored dots with no coherent image. This isn't a failure of technique but an inherent limitation of how optical mixing works. The paintings are designed for specific viewing distances where the dot structure resolves into blended color and recognizable forms. Get too close and you're below the critical distance where averaging occurs.

At close range, you see the individual brush marks, the texture of the canvas, the way paint sits on the surface in small dabs or stipples. What you don't see is the image. A face becomes a collection of pink, orange, white, and blue dots with no facial features visible. A tree dissolves into green, yellow, and purple spots that don't resolve into foliage. The representational content of the painting depends entirely on maintaining enough distance that optical mixing can occur.

This creates a strange viewing experience where the painting actively repels close examination. Most paintings reward looking closely, revealing brushwork, subtle color transitions, and technical details that aren't visible from across the room. Pointillist works do the opposite. Get closer and information decreases rather than increases. The optimal viewing distance is often surprisingly far, much farther than viewers naturally stand when looking at paintings in galleries.

The dot size determines the critical viewing distance. Smaller dots allow closer viewing before the image breaks down, but also require more meticulous application and longer painting time. Larger dots speed up execution but push the optimal viewing distance farther away. Seurat worked with relatively small dots in his major compositions, but even so, paintings like "A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte" need to be viewed from at least three or four meters away to resolve properly, and look better from even farther.

Gallery architecture often works against optimal viewing of pointillist paintings. Museum rooms aren't always large enough to allow the distances these paintings need. Viewers crowd around important works, positioning themselves close enough to read wall labels or see details, which is exactly the wrong distance for pointillist technique. The paintings end up viewed under conditions that prevent them from working as intended, which may be one reason pointillism looks less impressive in museums than reproductions sometimes suggest.

The close-range failure also reveals something about painting that pointillism sacrifices. Traditional painting techniques create visual interest at multiple scales. A Rembrandt rewards both distant viewing, where compositional structure and overall effect register, and close examination, where brushwork and paint handling become visible. Pointillism collapses this scalar richness, optimizing for one viewing distance at the expense of all others. You either see the image or you see dots, with no middle ground where both contribute to the experience.

Photography exacerbates this problem because cameras don't have the same distance-dependent blending that human vision does. Photographs of pointillist paintings either resolve the dots sharply, making the image disappear, or blur everything together, losing the distinctive pointillist quality. Reproducing these works effectively requires choosing a specific effective viewing distance and optimizing the photograph for that, which means photographic reproductions are always interpretations rather than straightforward documentation.

The close-range failure also makes pointillist technique impossible for certain subjects or scales. Miniature paintings can't use pointillism because the dots would need to be invisibly small. Works meant for intimate viewing don't suit the technique. The method only makes sense for relatively large paintings meant for viewing across room-sized distances, which limited its application to easel paintings and mural-scale works while excluding entire categories of image-making.

Seurat's Color Wheel and Simultaneous Contrast

Seurat constructed his own color wheel based on his reading of contemporary color theory, but it didn't quite match either the physics of light or the perceptual reality of pigment color. His wheel tried to map complementary relationships and color mixing predictions in ways that guided his palette choices and dot placement strategies. Understanding how this wheel worked and where it diverged from reality explains both pointillism's successes and its limitations.

The wheel positioned colors in relationships meant to indicate which combinations would create optical mixing effects and which would enhance each other through simultaneous contrast. Complementary pairs sat opposite each other: red-green, blue-orange, yellow-violet. Seurat believed placing complementary dots next to each other would create gray through optical mixing while simultaneously making both colors appear more intense through contrast. This paradox, wanting both mixing toward neutral and heightened intensity, was never fully resolved in the theory.

His practical application often ignored strict theoretical predictions in favor of what looked right. When theory suggested a combination would produce an undesirable result, Seurat adjusted rather than following the system rigidly. This pragmatic adaptation meant his best works succeeded despite theoretical inconsistencies rather than because of theoretical rigor. The systematic appearance of pointillist technique masked considerable empirical adjustment based on visual judgment.

Simultaneous contrast does create real perceptual effects that Seurat exploited effectively. When you place warm colors next to cool colors, each appears more intense. Orange next to blue looks more orange than orange next to red. This isn't optical mixing but mutual enhancement through contrast. Pointillist paintings use this extensively, creating chromatic intensity through strategic color adjacencies. The technique works, but it's operating through different mechanisms than the mixing theory suggested.

The color wheel Seurat used also reflected limitations of available pigments. He couldn't actually work with pure spectral colors because no pigments perfectly match spectral wavelengths. His "pure" colors were the most saturated pigments available, which meant his color wheel was really a pigment wheel mapping relationships between specific paints rather than an optical wheel mapping relationships between light wavelengths. Treating these as equivalent created systematic errors in his predictions about mixing results.

Warm-cool relationships in Seurat's work often succeed better than specific hue predictions. His use of warm and cool color zones to create depth, his modeling of form through temperature shifts, and his atmospheric effects all work perceptually even when the specific color theory behind them was questionable. This suggests he had strong intuitive understanding of color relationships that sometimes ran ahead of his theoretical framework.

The wheels and diagrams Seurat created look scientific, with precise divisions and systematic relationships. This appearance of rigor was important to the pointillist project's self-presentation as scientific painting. But the actual color relationships in his paintings don't map cleanly onto these diagrams. There's a performance of systematic scientific method that doesn't quite match the more intuitive color choices actually visible in the work. The theory provided justification and conceptual framework, but execution relied heavily on the same kind of visual judgment traditional painters used.

Later color theorists, working with better understanding of both optics and perception, have mapped how Seurat's wheel diverges from perceptual color space. His complementaries aren't exactly perceptual opposites. His mixing predictions don't align with what CIE color space would predict for the pigments he used. His simultaneous contrast effects work but not for the theoretical reasons he cited. The system was internally consistent enough to provide working guidelines but not rigorous enough to accurately predict perceptual results.

Practical Limitations of Pure Optical Mixing

Even when optical mixing works as well as the theory allows, it faces practical limitations that explain why pointillism never displaced traditional painting techniques. These limitations aren't just about execution difficulty but about fundamental constraints on what the technique can achieve compared to other approaches to paint application.

Color gamut restriction is the first major limitation. To maintain pure colors for optical mixing, pointillists avoided palette mixing, which meant they were limited to commercially available pigment colors plus whatever could be achieved through optical combination. Traditional painters could mix any intermediate color on the palette, creating subtle variations impossible to achieve through optical mixing alone. A traditional painter could mix fifty different greens. A pointillist using optical mixing might achieve ten or fifteen distinct greens, with much coarser gradations between them.

The execution time required for pointillist technique is enormous compared to traditional brushwork. Covering a canvas in small dots takes exponentially longer than applying paint in broader strokes. Seurat spent months or years on major compositions that a traditional painter might complete in weeks. This time investment limits productivity and makes the technique impractical for many painting contexts. You can't do quick studies or rapidly capture changing light effects when every square inch requires thousands of individual dots.

Subtle gradations and soft edges are difficult to achieve with distinct dots. Traditional painting can create infinitely smooth transitions through careful blending. Pointillism's granular structure means transitions happen in discrete steps, dot by dot. From appropriate viewing distance this creates acceptable smoothness, but it's coarser than traditional technique allows. Atmospheric effects, gentle modeling of form, and subtle color shifts all suffer from this quantization of the color field.

Dark colors pose particular problems for optical mixing. To create deep darks through optical mixing would require very dense dot placement with dark pigments, but this defeats the purpose since you might as well just paint the area dark directly. In practice, Seurat used traditional dark painting in shadows and only applied strict pointillist technique in lighter areas. This inconsistency undermines the systematic purity the technique claimed while acknowledging practical reality.

Surface texture from pointillist application can interfere with color perception. The physical paint dots create actual three-dimensional surface relief that catches light, creating highlights and shadows at micro-scale. This physical texture generates its own optical effects separate from the intended color mixing. Under raking light, pointillist surfaces can look very different than under even illumination, introducing viewing condition dependencies beyond what the theory accounted for.

Color intensity through optical mixing is limited by the subtractive nature of pigments. No matter how you arrange pigments spatially, you can't make them reflect wavelengths they don't reflect. The theoretical promise that optical mixing would create more intense colors than palette mixing doesn't hold because both ultimately depend on pigment reflectance properties. You might avoid some of the chromatic dulling that occurs when mixing physically incompatible pigments, but you can't exceed the fundamental limitations of available materials.

Conservation of pointillist works creates unique challenges. Because the effect depends on maintaining distinct dots at appropriate scales, any deterioration that softens edges or causes colors to bleed together destroys the technique's functionality. Traditional paintings can withstand certain types of degradation while remaining recognizable. Pointillist works are more fragile perceptually, requiring maintenance of precise surface characteristics to continue working as intended.

Scientific Color Theories Influencing Technique

Pointillism emerged during a period of intense scientific investigation into color perception, and Seurat tried to align his technique with contemporary color theory. Understanding which theories influenced him and where those theories have since been revised or superseded helps explain both what pointillism achieved and where it fell short of its ambitions.

Michel Eugène Chevreul's work on simultaneous contrast was foundational. Chevreul was director of dyes at the Gobelins tapestry works and investigated how adjacent colored threads affected each other perceptually. His observations about complementary colors enhancing each other and similar colors dulling each other provided practical guidelines that Seurat incorporated systematically. This part of pointillist theory has held up reasonably well since it described real perceptual phenomena rather than making false claims about color mixing.

Ogden Rood's "Modern Chromatics" provided Seurat with what seemed like scientific authority for optical mixing. Rood described how rotating discs of different colors blur into combined colors, which Seurat took as evidence that spatial juxtaposition of colors would produce similar optical combination. But rotating disc mixing is temporal averaging, not spatial averaging, and the mechanisms differ in important ways that Rood didn't fully understand. Seurat's extension of disc experiments to painting technique involved theoretical leaps that the science didn't actually support.

Charles Blanc's "Grammar of Painting and Engraving" synthesized various color theories into systematic rules for artists. Blanc emphasized complementary relationships and promoted the idea that scientific understanding of color would improve painting beyond traditional empirical methods. His work gave Seurat a framework for thinking about systematic color application, though Blanc himself didn't advocate pointillism specifically.

Hermann von Helmholtz's physiological optics research was probably known to Seurat indirectly through popularizations. Helmholtz investigated how the eye responds to colored light and established principles of additive color mixing that are correct for light but don't translate directly to pigment optics. Seurat seems to have confused additive light mixing with spatial pigment averaging, assuming principles that work for colored light projection would work for colored paint application.

James Clerk Maxwell's work on color perception and color photography established the trichromatic theory of vision, showing that all colors could be matched by combining three primary colored lights. This seemed to support the idea that all colors could be created through optical combination of primary pigments, but again the confusion between light and pigment led to overestimation of what optical mixing could achieve. Pigments don't combine additively the way colored lights do.

Later discoveries about color vision have revealed how much these nineteenth-century theories missed. The opponent process theory developed in the twentieth century shows that color perception involves not just three receptor types but complex neural processing that compares signals between receptors. Spatial context effects are far more sophisticated than simple averaging. Color constancy mechanisms adjust perceived color based on assumptions about illumination and surface properties. None of this was available to Seurat, who worked with a much simpler model of vision.

What's striking is how much pointillism succeeds despite working from partially incorrect theory. The paintings create effective color relationships and atmospheric effects not because the optical theory was right but because Seurat was a skilled painter who adjusted technique based on what looked right regardless of what theory predicted. The scientific framework provided confidence and systematic approach, but visual judgment determined actual color choices.

Modern color science would approach pointillism very differently, using CIE color space to predict mixing results, accounting for viewing condition dependencies through color appearance models, and acknowledging the limits of spatial averaging in creating new colors. A scientifically rigorous contemporary pointillism would look somewhat different from Seurat's work, probably using different color combinations and dot sizes optimized for actual perceptual effects rather than theoretical predictions.

The relationship between scientific theory and artistic technique in pointillism reveals something important about how artists use science. Seurat didn't just apply color theory mechanically. He interpreted it, adapted it, and supplemented it with traditional artistic judgment. The result was paintings that work aesthetically even when the underlying theory was questionable. This suggests that artistic success and scientific accuracy are separate achievements that sometimes align but don't necessarily depend on each other.

Photography Revealing What Technique Actually Achieves

Photographing pointillist paintings reveals the gap between theoretical intention and actual visual effect because cameras record different information than human vision processes. What a camera sees and what we see when looking at the same painting diverge in ways that expose the limitations of optical mixing theory while also showing what the technique genuinely accomplishes.

High-resolution photography of pointillist works resolves individual dots far more sharply than human vision does at normal viewing distances. This makes the photographs look very different from the perceptual experience of viewing the actual painting. In photographs, you see the dots, the canvas texture, the irregular paint application, all the physical surface reality that perceptual averaging smooths over when viewing the real object. This can make pointillist works look less impressive photographically than they are in person, since the photographs emphasize the mechanical dot structure over the optical effects.

Conversely, low-resolution reproduction or viewing photographs from distance can over-blend pointillist works, making them look like traditionally painted images without any visible pointillist structure. Early reproductions of Seurat in books often fell into this trap, smoothing everything together until the distinctive technique disappeared. The photographs needed to be high enough resolution that dot structure remained visible but low enough resolution or viewed from far enough distance that optical averaging still occurred. This narrow sweet spot makes pointillist works difficult to reproduce faithfully.

Spectral analysis of pointillist paintings through photography reveals what colors are actually present versus what colors are perceived. You can measure the reflectance spectra of individual dots and compare them to the perceived color of the area when viewed from appropriate distance. These measurements show that the perceived colors often don't match what additive mixing of the component wavelengths would predict, confirming that spatial averaging works differently than the additive mixing theory suggested.

Ultraviolet and infrared photography of pointillist paintings reveals underdrawing and preparatory work that normal viewing doesn't show. Many Seurat paintings have detailed preliminary drawings underneath the pointillist surface, showing he planned compositions traditionally before executing them in dots. This contradicts the spontaneous optical mixing idea and reveals the technique as a surface application method rather than a fundamental rethinking of how paintings are conceived and executed.

Raking light photography shows the physical relief of pointillist surfaces. The texture from dot application creates shadows and highlights that affect appearance in ways pure color theory doesn't account for. Under different lighting angles, the same painting can look substantially different as physical surface effects interact with color effects. Photography under controlled lighting reveals these dependencies that theory-driven description of the technique tends to ignore.

Time-lapse photography of viewers looking at pointillist paintings shows movement patterns that differ from viewing traditional works. People approach closely, then step back repeatedly as they try to find the optimal distance. They move side to side looking at how the image resolves differently at different angles. This active viewing behavior is part of the pointillist experience but isn't predicted by the static optical theory Seurat worked with. The paintings require viewer participation in finding the right viewing conditions to function as intended.

Digital manipulation of photographs of pointillist works can simulate what they would look like under different conditions. You can digitally change viewing distance, adjust individual dot colors, or alter dot size to see how these variables affect the perceptual result. This kind of analysis wasn't available to Seurat but retrospectively reveals which aspects of his technique contribute most to visual effects and which theoretical components matter less than he thought.

Comparing photographs of the same painting under different lighting conditions shows how much appearance varies with illumination. Color temperature of light sources, intensity, direction, all affect how the colors appear and how well optical mixing works. Photographs taken under daylight versus incandescent versus fluorescent lighting show dramatically different color relationships. The theory assumes invariant color properties that actual viewing conditions don't support.

What photography ultimately reveals is that pointillism creates effects that work perceptually under specific conditions but don't align cleanly with the theoretical framework that generated the technique. The paintings succeed as visual experiences, but for more complex and conditional reasons than optical mixing theory predicted. The gap between theory and photographic evidence highlights how artistic technique can work in practice while resting on questionable theoretical foundations.

Why Pointillism Never Became the Dominant Technique

If pointillism represented superior scientific understanding of color and vision, if it produced more luminous and vibrant results than traditional painting, why did it remain a brief historical experiment rather than becoming standard practice? The answer involves practical limitations, theoretical problems, and the simple fact that traditional painting techniques already solved the problems pointillism was trying to address, often more effectively and efficiently.

The execution time requirement alone would have prevented widespread adoption. Pointillism was prohibitively slow for any painting context requiring reasonable productivity. Portrait painters couldn't spend months on single commissions. Landscape painters couldn't use the technique for plein air work. Commercial illustration couldn't accommodate such time-intensive methods. The technique was only viable for independent artists with unusual patience or for specific works where meticulous execution was itself part of the point.

Traditional painting already achieved convincing color mixing and atmospheric effects without pointillist restrictions. Impressionists created vibrant, light-filled paintings using broken color techniques that allowed much more flexibility than strict pointillism. They could adjust their touch, vary paint application thickness, blend where needed and separate where desired. Pointillism's rigid systematic approach sacrificed the responsiveness that makes painting a versatile medium.

The theoretical advantages of optical mixing turned out to be largely illusory. Careful palette mixing by skilled painters could achieve any color effects that optical mixing produced, often with more control and subtlety. The promise of enhanced luminosity through optical mixing didn't materialize in practice because spatial averaging of pigments still obeys subtractive color rules. Traditional painters weren't giving up anything significant by continuing to mix colors on the palette.

Viewer response to pointillism was mixed at best. Some found the technique fascinating and appreciated its distinctive optical effects. Others found the paintings cold, mechanical, or overly systematic compared to the gestural vitality of traditional brushwork. The loss of individual touch and painterly spontaneity bothered viewers who valued those qualities in painting. Pointillism's scientific ambitions worked against the expressive freedom many people looked for in art.

Subsequent painting movements rejected pointillism's systematic approach in favor of more subjective color use. Fauvism used arbitrary colors for emotional effect. Expressionism prioritized psychological intensity over optical accuracy. These movements found pointillism's scientific framework limiting rather than liberating. The twentieth century moved away from the positivist faith in scientific rationalization that had made pointillism appealing in the 1880s.

The specific viewing distance requirements made pointillism impractical for many contexts. Paintings meant for small rooms, intimate viewing, or close examination couldn't use the technique effectively. This restricted pointillism to specific scales and viewing situations that limited its applicability. Traditional techniques work across all scales and viewing distances, from miniatures to murals, from immediate proximity to distant viewing.

Conservation challenges also counted against adoption. Pointillist surfaces are more vulnerable to deterioration that destroys optical effects than traditional painting surfaces. The technique requires maintaining precise surface characteristics indefinitely, which creates long-term preservation difficulties. Museums and collectors preferred techniques with better aging properties and easier conservation.

Educational transmission of the technique was difficult. Teaching pointillism required extensive time investment for students to master the systematic dot application. The theoretical framework was complex and based on color science that wasn't easily accessible. Traditional painting techniques could be taught more efficiently and allowed students to develop personal approaches more readily. Art schools never incorporated pointillism into standard curricula the way they did traditional methods.

The technique's association with a specific moment and specific artists also limited its spread. Pointillism was so identified with Seurat and Signac that using it seemed derivative rather than innovative. Other artists experimenting with the technique were seen as imitators. This wasn't inherent to the method but reflected how artistic innovation and influence work socially. Techniques that don't diffuse broadly beyond their originators tend to remain historical curiosities rather than becoming standard practice.

Economic factors played a role too. Pointillist paintings took so long to produce that they had to command high prices to justify the labor investment. This limited the market and made the technique viable only for artists who could support themselves during extended production periods. Traditional techniques allowed faster production and broader market participation.

Finally, pointillism solved problems that didn't need solving as urgently as its advocates believed. Traditional painting already achieved impressive color effects, convincing representation, and expressive power. Pointillism's alternative approach to these same goals offered few enough advantages that most painters reasonably concluded the traditional methods worked better. Innovation for its own sake wasn't compelling enough to overcome practical disadvantages.

What Pointillism Actually Teaches About Color

Despite its theoretical problems and practical limitations, pointillism did reveal genuine insights about color perception and paint application that remain relevant. The technique's failures are as instructive as its successes, and sorting through what worked from what didn't provides useful knowledge for anyone serious about understanding color in painting.

Simultaneous contrast effects are real and powerful. Pointillist paintings demonstrate clearly how adjacent colors affect each other's appearance. A neutral gray surrounded by red appears greenish. The same gray surrounded by green appears reddish. These effects occur regardless of whether optical mixing works as theorized. Understanding and exploiting simultaneous contrast improves color relationships in any painting technique. Pointillism makes these effects obvious in ways that traditional blended painting sometimes obscures.

Spatial separation of colors can create chromatic intensity that physical mixing dulls. Even if the mechanism isn't additive mixing, keeping colors distinct rather than blending them preserves their individual saturation. This principle works in broken color techniques, impressionist brushwork, and other approaches besides strict pointillism. The insight that you don't always need to blend colors to achieve desired effects is valuable across many painting contexts.

Viewing distance fundamentally affects color perception. This seems obvious but pointillism demonstrates it dramatically. The same painting surface produces entirely different perceptual experiences at different distances. Understanding this distance-dependent perception helps in making decisions about paint application scale, level of detail, and appropriate techniques for intended viewing conditions. Paintings meant to be seen from across a room can use broader marks than paintings meant for intimate viewing.

Systematic color organization can provide structure even when the underlying theory is questionable. Seurat's methodical approach to color placement, even if based on partially incorrect theory, created coherent color relationships throughout his compositions. The discipline of systematic thinking about color interactions has value independent of whether specific theoretical predictions are accurate. Many contemporary painters use personal color systems that organize their practice without claiming scientific validity.

Pigment properties limit what any technique can achieve. Pointillism's failure to exceed traditional mixing through optical combination confirms that you can't overcome fundamental material constraints through technique alone. Available pigments determine possible colors regardless of how you apply them. This reminds painters that material choice matters as much as application method. Better pigments enable better color regardless of technique.

Color theory requires validation through practice. Seurat believed his theoretical framework predicted results accurately, but actual paintings revealed where theory and perception diverged. This experimental approach, testing theoretical predictions against perceptual reality, is valuable even when the predictions turn out wrong. Contemporary color work benefits from similar empirical testing rather than accepting theoretical claims without verification.

The appearance of scientific rigor doesn't guarantee actual scientific accuracy. Seurat's systematic approach looked scientific with its color wheels, diagrams, and methodical technique. But looking scientific and being scientifically accurate are different achievements. This applies broadly to claims about art techniques based on color science. Technical-sounding explanations require critical examination rather than automatic acceptance.

Artistic success can diverge from theoretical accuracy. Seurat's best paintings work aesthetically even though the color theory behind them was partially wrong. The paintings prove that skilled visual judgment can overcome theoretical limitations. This suggests that understanding theory is useful but subordinate to perceptual sensitivity and aesthetic judgment. Theory guides but doesn't determine outcomes.

Practical constraints matter more than theoretical advantages in determining which techniques persist. Pointillism's theoretical promise wasn't compelling enough to overcome its execution difficulty, time requirements, and practical limitations. Techniques that work in practice under real-world constraints tend to persist regardless of theoretical elegance. This pragmatic test determines which innovations actually get adopted versus which remain interesting historical experiments.

The Distinction Between What Seurat Believed and What Actually Occurs

Understanding pointillism requires distinguishing clearly between what Seurat thought was happening and what vision science now reveals actually occurs when viewing his paintings. The gap is instructive about how artistic practice and scientific understanding relate to each other, often imperfectly.

Seurat believed he was creating additive color mixing through spatial juxtaposition of pure colors. He thought the eye would combine adjacent colored dots the way colored light beams combine, producing colors through addition of wavelengths rather than subtraction through pigment mixing. This was the core theoretical claim behind divisionism as scientific painting. It's also fundamentally incorrect as a description of what happens perceptually.

What actually occurs is spatial averaging of pigment reflectances within the visual system's resolution limits. The eye doesn't perform additive mixing. It averages the signals from a region of visual space when individual elements are too small to resolve separately. This averaging is still operating on pigment reflectance properties, which are fundamentally subtractive. The mechanism is different than Seurat imagined and the results are consequently different than he predicted.

Seurat thought pure spectral colors would produce more luminous mixtures than pigment mixing. But he wasn't working with pure spectral colors since no pigments perfectly match spectral wavelengths. He was working with the most saturated available pigments, which still had complex reflectance spectra. The assumed purity of his primaries was already compromised by material reality. This meant his predictions about mixture results were based on incorrect assumptions about starting materials.

He believed systematic application of color theory would make painting more scientifically rigorous and predictable. But his actual color choices in paintings involved extensive empirical adjustment based on what looked right rather than what theory predicted. The systematic appearance of pointillist technique masked pragmatic decision-making that contradicted strict theoretical application. The paintings succeeded because Seurat was a good painter who knew when to ignore his own theory.

Seurat thought viewing distance would simply determine whether optical mixing occurred or didn't, with a clear threshold between seeing dots and seeing blended colors. Actually, partial blending occurs across a range of distances with continuously varying perceptual effects. The relationship between viewing distance and color perception is gradual and complex rather than binary. This means his paintings don't have a single optimal viewing distance but rather a range where different effects occur.

He assumed color perception was relatively stable across viewing conditions and viewers. In reality, illumination, surrounding colors, individual differences in color vision, and contextual factors all substantially affect how the paintings appear. The perceptual results he achieved were more variable and condition-dependent than his theory acknowledged. Two viewers under different lighting conditions might have significantly different color experiences of the same painting.

Seurat believed simultaneous contrast and optical mixing would work together to enhance color intensity. But these are separate phenomena operating through different mechanisms. Simultaneous contrast does enhance perceived color saturation under appropriate conditions. Optical mixing through spatial averaging can create intermediate colors but doesn't necessarily increase intensity. Conflating these mechanisms led to unrealistic expectations about what pointillism could achieve.

He thought the technique would revolutionize painting by aligning it with scientific understanding of vision. Instead it remained a brief historical experiment that most painters rejected as impractical. The gap between theoretical ambition and practical adoption reveals how scientific rationale alone doesn't determine artistic technique viability. Practical constraints and aesthetic preferences matter more than theoretical sophistication in determining which methods persist.

What Seurat actually achieved was creating paintings with distinctive optical effects that work aesthetically through mechanisms he only partially understood. His success came from combining theoretical framework, systematic technique, and empirical adjustment based on visual judgment. The theory provided structure and confidence. The systematic technique created consistency. The empirical adjustment made it actually work.

This pattern, where artistic innovation proceeds from partially incorrect theory through pragmatic adaptation to successful practice, is common in art history. Alberti's linear perspective theory had mathematical errors. Impressionist ideas about simultaneous perception weren't quite neurologically accurate. Color field painting's claims about pure optical experience ignored contextual factors. Theories provide direction and justification while practice determines actual results.

Understanding this gap for pointillism is useful not primarily as historical correction but as reminder that how paintings work and why artists think they work can be separate questions. The mechanisms producing visual effects may differ from theoretical explanations without invalidating the effects themselves. Appreciating pointillist paintings doesn't require accepting Seurat's color theory. Understanding why the theory was wrong doesn't diminish the paintings' aesthetic success.

The contemporary relevance is in recognizing that claims about artistic technique based on color science require critical examination. Current theories about color perception are more sophisticated than nineteenth-century knowledge but still incomplete. Artists working with color theory today should test theoretical predictions against perceptual reality rather than assuming scientific-sounding claims are necessarily accurate. Pointillism's history shows that empirical verification matters more than theoretical elegance.