Research Methods for Artists Who Want More Than Visual Inspiration

Pinterest gives you aesthetics but not ideas. Real artistic research means reading outside art, testing materials systematically, visiting archives, conducting interviews, and building knowledge that transforms your work from attractive to substantive.

You're scrolling through Pinterest again, saving images of work that looks interesting, copying color palettes, bookmarking compositions you like. Your folders are full of visual references but when you sit down to make work, you realize you're just remixing other people's aesthetics. You have influences but not ideas. You have style references but not substance. You know what you want your work to look like but not what you want it to actually be about.

This is the Pinterest problem. Visual platforms give you endless aesthetic inspiration but do nothing to help you develop genuine conceptual depth. They show you surfaces without showing you the thinking, the research, the intellectual engagement that makes work substantive rather than just attractive.

Real research for artists isn't about collecting pretty pictures. It's about investigating questions, following ideas into unfamiliar territory, building knowledge that transforms your understanding and therefore transforms your work. It's reading, interviewing, visiting archives, testing materials, documenting processes, thinking through making and making through thinking. It's actual intellectual labor that generates concepts worth spending months or years exploring.

Understanding how to research as an artist, what methods serve artistic practice versus academic practice, and how to turn research into concepts that sustain bodies of work moves you from making attractive individual pieces to developing rigorous artistic practice with real depth.

What Artistic Research Actually Is

Research in art practice differs fundamentally from academic research but shares the goal of generating new knowledge or understanding through systematic investigation.

Academic research typically aims to produce generalizable knowledge, findings that apply beyond specific cases. Scientific research discovers principles. Humanities research builds arguments supported by evidence. The research exists independently of the researcher and gets communicated through papers, presentations, publications.

Artistic research generates knowledge through and for artistic practice. The research might be highly specific to your particular questions, materials, or concerns. It doesn't need to generalize. It needs to deepen your work. The research and the artwork are intertwined; the research informs making and making reveals what else you need to research.

Some artistic research becomes the artwork itself. Mark Dion's archaeological digs and cabinet installations are research practice as art practice. The investigation, collection, categorization, and display are simultaneously research and artwork. The boundary between research and art-making dissolves.

Other artistic research remains behind the scenes, informing work without being visible in final pieces. Your research into historical textile techniques might generate ideas for contemporary work that looks nothing like historical textiles. The research serves the work without being the work.

Both approaches are legitimate. The question is whether your research needs to be visible to viewers for the work to succeed or whether it's generative tool for your own practice.

Research questions for artists are often open-ended and might not have definitive answers. You're not trying to prove a hypothesis. You're investigating territory, following curiosity, building understanding that generates more questions. The research succeeds when it deepens your engagement with your subject, not when it reaches conclusions.

Artistic research often combines methods from multiple disciplines. You might read philosophy, conduct ethnographic interviews, test materials scientifically, explore archives, all for a single project. The interdisciplinary promiscuity of artistic research is strength, not weakness. You take what serves your questions from wherever it exists.

The timeline for artistic research is usually longer and less defined than academic research. You might research intermittently over years as ideas develop. Research and making cycle back and forth rather than research happening first and making happening after. This iterative, open-ended process reflects how artistic thinking actually works.

Documentation of artistic research looks different than academic documentation. You might keep studio notebooks mixing sketches, quotes, material tests, and thoughts rather than formal research notes. Your documentation serves your making process, not external evaluation. It can be messy, associative, visual, and non-linear.

The key distinction is that artistic research serves artistic ends. You're not trying to contribute to an academic field or build scholarly arguments. You're building understanding that makes your artwork more substantive, more grounded, more capable of generating meaning beyond surface aesthetics.

Primary Research Methods for Studio Practice

Primary research involves generating new information through direct investigation rather than relying only on existing sources. For artists, this often means hands-on investigation.

Material testing and experimentation is primary research. When you systematically test how different pigments behave in your medium, you're researching. When you document how materials age under different conditions, you're researching. This empirical investigation generates knowledge specific to your practice.

Keep systematic records of material experiments. Photograph results, note proportions and conditions, document failures and successes. This creates knowledge base you can return to rather than relying on memory. Your testing becomes research when it's documented and analyzed, not just random experimentation.

Site visits and direct observation generate information unavailable through secondary sources. If you're making work about a specific place, visiting that place and documenting it through photos, sketches, notes, and sensory attention creates primary source material for your work.

Observe systematically, not just casually. Take time to notice patterns, changes over time, details that aren't obvious initially. Return multiple times if possible. Direct sustained observation reveals things casual looking misses.

Interviews and oral histories capture knowledge that might not exist in written form. Talking to people who have relevant experience, expertise, or perspective gives you information and understanding you can't get from books or internet searches.

Prepare interview questions in advance but follow interesting tangents that emerge. Record interviews if possible so you can review them later. Transcribing key sections creates text you can reference in your work or research notes.

Performance of processes or practices, actually doing the thing you're researching, generates embodied knowledge. If you're interested in historical craft techniques, learning and practicing those techniques teaches you things reading about them can't. The physical doing is research.

Document your process learning through video, photos, or detailed written descriptions. The documentation captures not just results but also challenges, failures, discoveries you make through doing.

Creating archives of collected materials, objects, images, or texts related to your research builds resource specific to your interests. Unlike using existing archives, creating your own allows you to organize materials according to your conceptual framework.

Your personal archive might mix found objects, photographs you've taken, printed texts, sketches, material samples, anything relevant to your research questions. The collection and organization process is itself generative thinking.

Mapping and diagramming relationships between ideas, materials, or phenomena makes connections visible and generates new insights. Mind maps, flow charts, relationship diagrams, all help you think through complex information and see patterns.

These visual thinking tools work particularly well for artists because they're spatial and visual rather than purely linguistic. Drawing connections between concepts often reveals relationships that linear writing obscures.

Repeated action or sustained engagement with specific subjects over extended time generates understanding through duration and attention. This might be daily drawing practice focused on specific subjects or long-term photography project or sustained observation of changing conditions.

The research value comes from sustained attention revealing things brief encounters miss. Change over time, subtle variations, deeper understanding all emerge through durational engagement.

Secondary Research That Actually Matters

Reading and engaging with existing sources remains crucial even though it's less hands-on than primary research. But reading strategically for artistic research differs from academic reading.

Follow your questions, not curriculum. You're not trying to comprehensively understand a field. You're pursuing specific questions, so read what addresses those questions even if it means jumping between disciplines and ignoring large bodies of literature.

Start with overviews and introductions to get oriented, then follow citations and references to more specific sources. The footnotes in one useful source often lead to other useful sources. This citation chain following is efficient way to find relevant material.

Read outside art entirely. Philosophy, history, science, sociology, anthropology, literature, all contain ideas and information relevant to artistic practice. Some of the most generative research happens when you bring ideas from other fields into your art-making.

Don't read to accumulate facts. Read to encounter ideas that generate more ideas, to find frameworks for thinking, to discover language for what you're trying to do. The value is in how reading changes your thinking, not in what you memorize.

Take notes that connect reading to your work. Write down quotes that resonate, ideas that spark connections, questions that emerge. Your notes should be in conversation with your studio practice, not just summaries of what you read.

Academic journals in fields related to your interests contain current research and theoretical discussions. Many journals have some open-access articles available free online. Google Scholar helps locate relevant papers across disciplines.

Museum and gallery publications often include essays contextualizing work historically and theoretically. Exhibition catalogs can be expensive but often contain substantial critical writing alongside images. University libraries usually have extensive collections.

Artists' writings and interviews reveal how working artists think about their own practice. Reading artist statements, interviews, and published writings gives insight into artistic thinking that criticism or history doesn't always capture.

Documentary sources like historical newspapers, letters, diaries, or records provide period perspective and detail. If you're researching historical subjects or contexts, primary sources from the period offer understanding contemporary sources can't match.

Technical and practical sources, craft books, material science texts, engineering references, all contain information artists can use even when those sources aren't written for artistic audiences. The technical information becomes raw material for artistic thinking.

Theory and critical writing provides frameworks for understanding culture, meaning, power, representation. You don't need to become theorist but familiarity with key theoretical ideas helps you think through what your work does and means.

Don't get trapped in reading at the expense of making. Research and making should feed each other. When reading stops generating ideas for studio work and becomes procrastination or anxiety about not knowing enough, step away and make something.

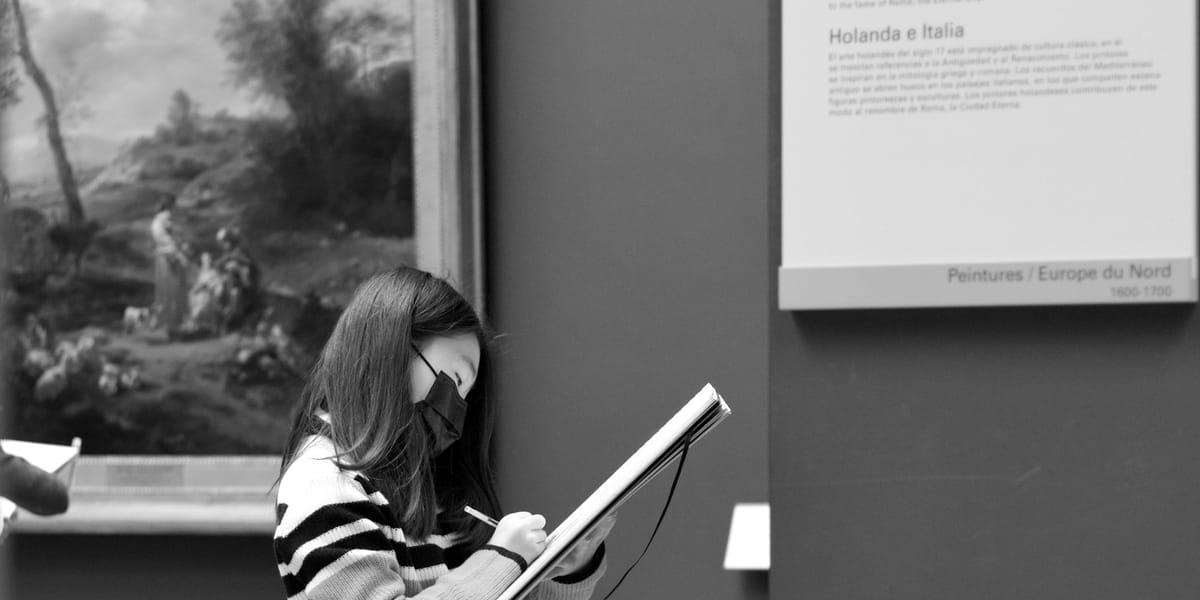

Archives and Special Collections

Archives contain unique primary source materials not available elsewhere, making them valuable research sites for artists interested in historical subjects or materials.

University special collections hold manuscripts, rare books, photographs, personal papers, and other archival materials. Many universities allow public access by appointment. Contact the special collections library to inquire about access and relevant holdings.

Museum archives contain materials related to their collections: correspondence, acquisition records, provenance research, conservation reports. Access policies vary but many museums accommodate serious research requests.

Government archives at local, state, and federal levels contain public records, maps, photographs, official documents. The National Archives in the US holds massive collections of federal government materials. State and local archives hold regional materials.

Organizational archives from businesses, institutions, or associations preserve records of their activities and often include photos, products, correspondence, or other materials relevant to artists researching those subjects or periods.

Personal collections and family archives contain materials passed down through families: letters, photos, documents, objects. If you're researching family history or have access to relevant family collections, these can be rich sources.

Digital archives increasingly make materials accessible remotely. Many institutions have digitized portions of their collections. Digital archives allow preliminary research before visiting physical archives or provide access when visits aren't possible.

Working in archives requires different skills than library research. Materials are unique and fragile. Access is controlled. You work with original documents, photographs, or objects under supervision. Archival research feels more like detective work than library research.

Before visiting archives, research their holdings online and contact archivists about your interests. They can guide you to relevant materials and explain access procedures. Archivists are knowledgeable and often helpful if you explain your research clearly.

Handle archival materials carefully following all institutional guidelines. Use pencil never pen. Don't lean on documents. Ask before photographing. Respect the materials; they're irreplaceable.

Take systematic notes and photographs (when permitted) of materials. You can't check out archival materials, so your documentation during the visit is what you take away. Photograph full documents plus details you'll want to reference later.

Archival research generates questions as much as answers. You discover unexpected materials, make connections between items, encounter information that changes your understanding. Follow these leads even when they diverge from initial research plans.

Using archival materials ethically means respecting privacy, copyright, and cultural sensitivity. Personal letters, private documents, culturally significant materials all require thoughtful handling. Just because archives grant access doesn't mean everything should be publicly shared in your work.

Integrating archival materials into artwork requires considering how to credit sources and respect archival contexts. Some artists reproduce archival materials directly. Others reference them more abstractly. How you acknowledge archival research in your work varies with your approach.

Ethnographic and Social Research

When your work engages with communities, cultures, or social phenomena, ethnographic methods help you understand contexts and perspectives beyond your own experience.

Participant observation involves engaging with communities or activities you're researching while documenting and analyzing your experience. This is standard ethnographic method anthropologists use. Artists can adapt it for artistic research.

If you're making work about specific labor, practice, or culture, spending time participating in those contexts generates understanding that outside observation can't provide. The embodied knowledge from doing alongside people you're researching matters.

Document your participant observation through field notes, photos, video, sketches, whatever captures experience and reflections. Note not just what happens but your reactions, questions, and developing understanding.

Respect boundaries and relationships. If you're in communities as researcher/artist, be clear about that. Don't extract knowledge without giving back. Consider how your presence affects what you observe. Ethical engagement matters.

Collaborative research with communities you're working with transforms research from extractive to participatory. Instead of researching about people, research with them. This changes power dynamics and often produces richer understanding.

Collaboration might mean conducting research together, sharing findings, creating work collaboratively, or having community members direct the research questions. The form depends on the project and relationships.

Long-term engagement rather than brief visits generates deeper understanding. Ethnographers typically spend months or years in field sites. Artists can't always commit that time but longer engagement produces better research than quick extractive visits.

Understanding social and cultural contexts requires reading anthropology, sociology, history, and cultural studies related to the communities or phenomena you're researching. Combine your direct research with scholarly understanding of relevant contexts.

Reflexivity, awareness of how your own position, biases, and perspective shape your research, is crucial in social research. You're not neutral observer. Your identity, background, and assumptions affect what you see and how you interpret it. Acknowledging this doesn't eliminate bias but makes it visible.

Power dynamics in research relationships matter enormously, particularly when researching marginalized communities or cultures not your own. Who benefits from this research? Whose voice gets amplified? Who controls how information is used? These questions have ethical and political dimensions.

Consent and representation require ongoing attention. Getting permission to research or document doesn't mean people consented to any use you might make of that information. Ongoing communication about how you're representing people and communities prevents exploitation.

Some subjects and communities shouldn't be researched by outsiders or should only be engaged with extreme care and respect. Cultural appropriation concerns are real. If you're researching cultures not your own, particularly indigenous or marginalized cultures, understand the politics and ethics deeply before proceeding.

Material Research and Testing

For artists whose work is materially focused, systematic investigation of material properties and behaviors is primary research method.

Controlled testing isolates variables to understand specific material properties. If you want to know how a pigment performs under UV exposure, you test that pigment against others under identical conditions and document results over time.

Set up tests that answer specific questions. What happens to this material when it dries? How do these materials bond? What colors mix to create that effect? The more specific your question, the more useful your test results.

Document everything systematically. Photograph tests at intervals. Record exact materials and proportions. Note conditions like temperature and humidity. Systematic documentation turns casual experimentation into research.

Accelerated aging tests compress time to predict long-term material behavior. UV chambers, heat cycling, freeze-thaw testing all simulate years of exposure in weeks or months. These tests help you understand how materials will age without waiting decades.

Combination testing explores how different materials interact. What happens when you layer these? Do these adhere? How do these expand and contract relative to each other? Material compatibility research prevents future failures.

Failure testing pushes materials to breaking points to understand limits. How thin can this be before it cracks? How much weight will this support? Where does structural failure occur? Understanding failure modes informs design.

Surface treatment testing compares finishing options. How do different sealers perform? Which paint adheres best? What coating provides the protection you need? Testing before committing to final work prevents mistakes.

Environmental testing subjects materials to conditions they'll face in use. If work will be outdoors, test materials under outdoor conditions. If work will be handled, test handling effects. Simulate actual use conditions.

Archival testing for permanence matters if you're concerned about longevity. Lightfastness tests, chemical stability tests, degradation tests all provide information about how materials will survive over time.

Comparative testing between materials helps you choose optimal materials for specific applications. Testing multiple options side by side reveals relative performance that isolated tests might miss.

Keep sample archives of tested materials labeled with dates, conditions, and results. These samples become reference library showing how materials age and perform over time.

Material research often reveals unexpected behaviors that become aesthetic or conceptual elements in your work. The research discovers material properties you can exploit artistically.

Synthesis and Analysis

Research generates information but understanding requires synthesis and analysis that transform information into usable knowledge.

Pattern recognition across different research sources reveals connections and themes. When the same ideas, forms, or concerns appear repeatedly in different contexts, pay attention. These patterns suggest significant relationships.

Create systems for organizing research materials so you can see relationships. This might be physical pinboards with clusters of related materials, digital folders organized by theme, or databases tagging materials by multiple categories.

Writing through your research helps clarify thinking. Don't wait until you understand everything to write. Write to think, writing to discover what you understand and what still confuses you. Studio notes, research journals, drafts, all help you process information.

Synthesize across disciplines and sources. What connections exist between the history you're reading, the materials you're testing, the interviews you've conducted? Cross-pollinating insights from different research streams generates new understanding.

Visual synthesis through drawings, diagrams, collages, or moodboards helps artists process research visually. Create visual maps of connections, sketch out relationships, collage research materials together to see how they interact.

Discussion with others tests and develops your thinking. Talking through research with other artists, friends, advisors, anyone willing to engage helps you articulate ideas and discover gaps or inconsistencies.

Return to your original questions periodically. Has your research answered them? Generated new questions? Revealed the original questions were wrong? Research that doesn't circle back to questions risks becoming accumulation without direction.

Identify gaps in your understanding where you need more research. Every research project reveals what you don't know. Making those gaps explicit helps you decide where to research next.

Look for contradictions and tensions in your research. When sources disagree or materials behave unexpectedly, that tension is often more generative than smooth agreement. Contradictions reveal complexity worth exploring.

Question your assumptions and interpretations. Are you seeing what's actually there or what you expect to see? Checking your interpretation against other perspectives prevents confirmation bias.

Create research summaries for yourself documenting key findings, important sources, and insights. These summaries become resources you can reference when making work without having to review all research materials.

Allow time for incubation. Some understanding comes from sitting with research, letting it percolate, coming back to it with fresh perspective. Not all synthesis happens immediately through active analysis.

Turning Research Into Concepts

Research generates information and understanding but conceptual development requires moving from knowledge to artistic questions and approaches.

Identify genuine questions your research raises, questions you don't already know answers to and that could sustain sustained investigation. These become potential conceptual territory.

Good artistic concepts are open-ended enough to explore through multiple works but specific enough to provide direction. "I'm interested in memory" is too vague. "I'm investigating how material degradation functions as physical memory" is specific enough to work with.

Your research should complicate rather than simplify your understanding. If research just confirms what you already thought, you probably haven't researched deeply enough. Complexity is generative.

Look for contradictions, paradoxes, or tensions your research revealed. These often become rich conceptual territory because they resist easy resolution. Work that engages complexity is usually more interesting than work that presents simple conclusions.

Connect research to formal and material concerns. How does what you've learned inform how you make work? What materials, processes, or forms emerge from your research? Concept and making should inform each other.

Some research suggests specific approaches. Historical textile research might lead to working with fabric. Material research into rust might lead to using corroding metals. Let research guide you toward appropriate media.

Test conceptual ideas through small initial works before committing to large projects. Make sketches, studies, experiments that explore whether research ideas actually work as art ideas. Not all interesting research translates to compelling artwork.

Be willing to abandon research that isn't generating artistic possibilities. Some fascinating research just doesn't connect to making. That's fine. The research might inform future work or it might just be interesting tangent.

Share research and emerging concepts with trusted people who can give thoughtful feedback. Explaining your thinking to others often clarifies it for yourself and reveals where concepts need development.

Write artist statements or project proposals articulating your concepts. The writing forces clarity and reveals conceptual gaps. Even if the writing never gets published, the process develops your thinking.

Remember that concepts develop through making, not just thinking. Sometimes you have to make work to understand what your concept actually is. The making is thinking. Research informs making but doesn't replace it.

Building Research Practice Over Time

Sustainable research practice integrates with rather than interrupts your studio practice.

Create regular research time rather than intensive bursts. An hour or two weekly reading, visiting sites, or organizing materials is more sustainable than irregular marathons.

Build research infrastructure: filing systems, note-taking practices, ways of organizing materials that work for you. Good systems make research cumulative rather than scattered.

Develop relationships with resources: libraries, archives, material suppliers, communities you're researching. These relationships make future research easier and often lead to unexpected opportunities.

Keep running lists of research questions, interesting sources, things to investigate. When you have research time, consult these lists rather than starting from scratch deciding what to research.

Balance broad exploratory research with focused project-specific research. Both are valuable. Exploration generates new interests. Focused research serves active projects. Alternate between them.

Document your research process not just your findings. Knowing how you found information helps you find similar information later. Your research methods become replicable and improvable.

Create research archives for each project: folders, boxes, or digital collections containing all materials related to specific bodies of work. This organizes research and creates reference for future related work.

Accept that research is ongoing and incomplete. You'll never know everything about your subjects. At some point you know enough to make work. More research can always happen but don't let endless research delay making.

Share research with other artists. Teaching others what you've learned, writing about research, giving talks, all deepen your own understanding while contributing to broader artistic community.

Stay curious. The best research comes from genuine curiosity about subjects, not from obligation or resume building. If your research feels like homework, you're probably researching wrong topics.

Common Research Failures and How to Avoid Them

Artists make predictable research mistakes that understanding helps prevent.

Over-researching to avoid making is procrastination disguised as productivity. If you're reading your tenth book on the subject without making any work, research has become avoidance. Make something, even imperfectly, to reconnect research with practice.

Researching to prove predetermined conclusions rather than genuinely investigate means you're not really researching, you're supporting existing ideas. Real research might challenge what you thought you knew. Be open to that.

Superficial research from only Wikipedia or general internet searches doesn't generate depth. These sources are starting points, not destinations. Follow leads to more substantial sources.

Letting research dictate work rather than inform it creates illustration of research rather than work generated by research. Research should raise questions and suggest possibilities, not provide blueprints.

Academic language obscuring actual ideas happens when artists adopt theoretical jargon without understanding it or without genuine need for that language. Complexity in thinking doesn't require complexity in language.

Research as credibility performance, displaying research to prove seriousness rather than because it serves the work, creates work weighed down by unnecessary citation and reference. Research that matters to your work doesn't need to be performed for viewers.

Narrow disciplinary research misses valuable connections. If you only read art theory, you miss insights from other fields. Promiscuous interdisciplinary reading generates unexpected connections.

Ignoring relevant research because it seems too difficult or outside your field limits your development. Challenge yourself to engage with complex material even when it's hard. The difficulty often indicates importance.

Cultural appropriation through research, taking from cultures you don't belong to without permission, respect, or understanding, is serious ethical failure. If you're researching cultures or communities not your own, do so with extreme care and respect.

Forgetting that research serves making leads to research becoming end in itself. If research doesn't eventually inform your artwork, it might be interesting but it's not artistic research.

Research as Ongoing Practice

Building research into regular practice rather than treating it as separate from making creates sustainable integration of thinking and doing.

Studio time includes research time. Don't separate making days from research days. Integrate reading, testing, documenting, organizing into regular studio practice.

Follow curiosity wherever it leads. When something in your work raises questions, pursue those questions. The research questions that emerge from making are often most valuable.

Research deepens over time through sustained attention to subjects. Quick shallow engagement generates quick shallow understanding. Commit to subjects long enough for real depth to develop.

Your research practice will evolve as your work evolves. Methods that serve one body of work might not serve the next. Stay flexible and willing to learn new research approaches.

Share knowledge and cite sources. When your research informs work, acknowledge important sources in statements, didactics, or publications. This honors the knowledge workers whose work you're building on.

Research makes you a better, more informed, more intellectually engaged artist. It doesn't guarantee better artwork but it provides foundation for work with substance beyond surface aesthetics.

The goal isn't to become scholar or academic. The goal is to develop artistic practice grounded in genuine investigation, curiosity, and understanding. Research transforms you from someone who makes things that look interesting into someone whose work actually has something to say.

When you stop relying on Pinterest for ideas and start building actual knowledge through reading, visiting, testing, interviewing, and thinking, your work changes. It develops authority that comes from genuine engagement with subjects. It gains depth that can't be faked. It becomes yours in ways that borrowed aesthetics never are.

Research isn't the work itself. Making is the work. But research transforms what making can be, opening possibilities and generating understanding that makes your work substantive, grounded, and capable of meaning beyond what any amount of technical skill alone could achieve.