When Artists Know a Work Is Finished

Artists decide when work is finished through intuition, systematic rules, or deadline pressure. Each approach reveals different relationships to completion.

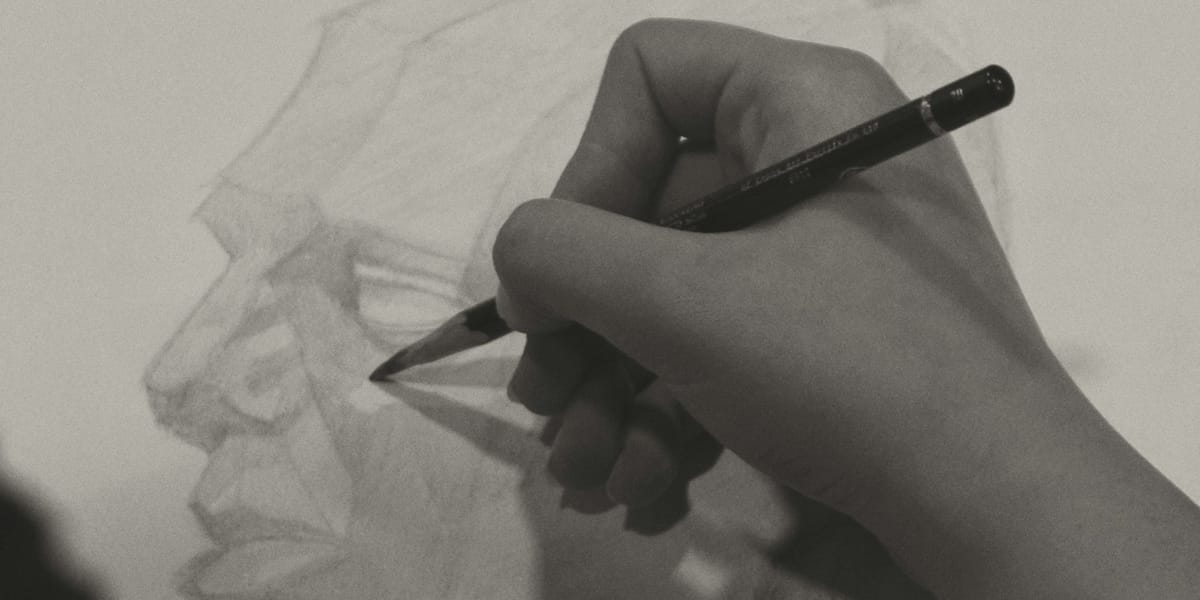

There's a moment in every artist's process that outsiders find mystifying: deciding the work is done. Not abandoned out of frustration or boredom, but actually complete—ready to leave the studio, to be seen, to exist independently. How do they know?

It's a question without universal answer because artists approach completion as differently as they approach everything else. Some report near-physical certainty, an unmistakable feeling that adding or changing anything would diminish rather than improve. Others follow systematic rules they've developed through years of practice. Still others never quite finish but rather reach points where continuing feels less productive than moving on.

Understanding how artists navigate this fundamental decision reveals something essential about creative process and the nature of artistic judgment. It also helps viewers appreciate that the work they encounter represents not just what artists made but also what they chose to stop making.

The Intuitive Approach

Many artists describe completion as something they simply feel rather than consciously decide. After hours, days, or months of working, something shifts. The piece feels done. This intuitive certainty comes not from mystical inspiration but from accumulated experience and tacit knowledge about their own practice.

Painter Helen Frankenthaler spoke of completion as recognizing when a work achieved its own internal logic and balance. She couldn't articulate precise criteria but trusted her eye and instinct developed over decades. The painting would tell her, in effect, when it was ready.

This intuitive approach doesn't mean casual or unconsidered. Artists working this way have internalized vast amounts of knowledge about composition, color, form, and their own aesthetic standards. The intuition represents rapid processing of complex visual information too subtle and multifaceted for conscious analysis.

What they're sensing often involves multiple factors happening simultaneously: compositional balance achieved, color relationships resolved, formal tensions finding equilibrium, the work gaining sense of inevitability where nothing feels arbitrary or unresolved.

Sculptor Richard Serra described knowing his massive steel works were complete when they achieved what he called "rightness"—a quality impossible to define but unmistakable when present. This rightness involved spatial relationships, material presence, and formal qualities all aligning in ways that felt necessary rather than merely chosen.

For artists working intuitively, the risk lies in either stopping too soon, before the work fully develops, or continuing past the point of completion, overworking and losing whatever quality made it successful. Learning to recognize that precise moment of completion becomes crucial skill that develops slowly through repeated practice and occasional failures.

Some intuitive finishers describe a shift in their relationship to the work. While creating, they're actively problem-solving, making decisions, pushing toward something. At completion, this active engagement suddenly feels inappropriate. The work no longer needs them. It's become itself, independent and complete.

This shift can happen gradually over final sessions or arrive suddenly in single moment. Painter Philip Guston talked about working furiously for hours, then stepping back and realizing abruptly that he was done, that anything more would be revision rather than development.

Working to Predetermined Criteria

Other artists establish clear completion criteria before or during creation. These rules might be formal (certain number of layers, specific technical processes completed), conceptual (particular idea fully expressed), or systematic (following predetermined plan to conclusion).

Minimalist and conceptual artists often work this way. Sol LeWitt's wall drawings followed instructions that, once executed completely, meant the work was finished. There was no intuitive judgment about when to stop; the system itself determined completion.

Contemporary painter Amy Sillman describes sometimes setting herself specific tasks or problems to solve. When the problem is addressed or the task completed, the painting is done. This approach brings clarity to what otherwise might feel endlessly uncertain.

The predetermined criteria might be simple. Painter Agnes Martin worked in six-foot squares with horizontal lines. Once the square was filled according to her system, the work was complete. This limitation paradoxically freed her from anxious questioning about when to stop.

For process-based artists, completion might simply mean the process has run its course. If you're allowing paint to drip, gravity determines when dripping stops. If you're documenting something over specific duration, time marks completion. The work finishes when the process finishes.

This systematic approach provides psychological relief from the burden of intuitive judgment. Instead of agonizing over whether to add more or change something, you follow the rules you established. The criteria do the deciding.

However, artists working this way often maintain escape clauses. If following the system produces clearly unsuccessful result, they allow themselves to abandon or adjust rather than considering it complete just because the rules say so. The system guides but doesn't absolutely determine.

Some artists develop personal completion checklists, either mental or literal. Does the work accomplish what I intended? Have I addressed the formal problems I identified? Would adding anything improve it or just fill space? Does it feel necessary rather than arbitrary? These questions provide framework for systematic evaluation.

The advantage of criteria-based completion lies in reducing the anxiety and uncertainty that can paralyze decision-making. The disadvantage is potentially missing intuitive insights that couldn't be anticipated when establishing rules. The best systematic approaches balance predetermined criteria with openness to what the work itself suggests.

The Deadline as Forcing Function

For many working artists, completion often coincides with external deadlines. The exhibition opening approaches, the commission is due, the residency ends. Ready or not, the work must be finished.

This pragmatic reality shapes completion in ways both productive and problematic. Deadlines force decisions that might otherwise be delayed indefinitely. They prevent the endless tinkering and revision that can become procrastination disguised as perfectionism.

Many artists admit they wouldn't finish work without deadlines. The pressure creates urgency that overcomes doubt and hesitation. Gallery director needed to see work by Friday means it's finished Thursday night, regardless of whether it feels completely resolved.

Some artists deliberately create artificial deadlines even without external pressure. They tell someone they'll show the work by certain date, knowing this commitment will force completion. Without this external structure, they might revise endlessly.

The deadline-driven approach raises questions about whether work is genuinely finished or merely stopped. Is there meaningful difference? Some artists argue that completion is always somewhat arbitrary, that work could potentially continue indefinitely, so external deadlines just formalize what would happen eventually anyway.

Others distinguish between work that feels complete and work that's merely stopped. Deadline-finished work might feel premature, not fully developed, or missing something. This can create dissatisfaction even when the work succeeds by other measures.

Interestingly, deadline pressure sometimes produces unexpected breakthroughs. The urgency and focused attention can cut through overthinking and self-consciousness. Artists report sometimes doing their best work in deadline's final push, accessing directness and clarity that earlier, more relaxed working lacked.

Sculptor Anish Kapoor has discussed how exhibition deadlines force commitment to decisions that felt uncertain or provisional. Without the deadline, he might continue questioning and adjusting. The deadline says "this is what it is," transforming tentative into definite.

For artists working in time-intensive media like oil painting or cast sculpture, deadlines require careful planning. Completion must be anticipated weeks or months before deadline to allow for technical processes like drying or fabrication. This forward-planning changes how they think about finishing.

The relationship with deadlines evolves over careers. Early-career artists often feel tyrannized by them, rushing to complete work that feels unfinished. Established artists learn to plan backwards from deadlines, building in time for completion to happen more organically.

Some artists deliberately avoid deadline pressure, refusing exhibition commitments until work reaches natural completion. This requires financial stability and confidence that might not be available to everyone, making it somewhat privileged position.

The Serial Revisers

Some artists struggle with completion to the point where it becomes ongoing challenge rather than occasional difficulty. These serial revisers continue working on pieces long after others would consider them done, sometimes never fully releasing work from revision's possibility.

Painter Frank Auerbach famously scraped down and repainted the same canvases repeatedly, sometimes working on single painting for years. Each session might obliterate previous day's work. Completion for him meant less deciding the painting was finished than accepting it was as good as he could get it at that moment.

This approach can produce remarkable results through accumulated layers and revisions, each round incorporating insights from previous attempts. The work gains depth and complexity impossible to achieve in single campaign.

However, serial revision also risks overworking, losing spontaneity or directness that made earlier versions successful. Knowing when continued revision improves versus when it just changes or even degrades requires difficult judgment.

Some revisers develop strategies to protect against endless adjustment. They photograph work at various stages so they can return to earlier versions if revision goes wrong. They establish stopping rules even while feeling uncertain. They seek outside opinions to counter their own compulsive tinkering.

The underlying issue often involves difficulty accepting imperfection or trusting initial impulses. The work could always be better, problems could always be solved, so why stop? This perfectionism can be valuable in pushing toward higher standards but destructive when it prevents ever finishing.

Interestingly, viewers often can't detect the difference between work the artist considers finished and work they felt forced to abandon incomplete. What reads as complete from outside may feel unresolved from inside. This suggests that completion is partly about artist's psychological state rather than work's objective qualities.

Some revisers eventually recognize that their dissatisfaction with finished work isn't really about the work but about themselves. No matter how much they revise, they'll find something to improve. At some point, accepting this pattern allows moving on even with reservations.

Sculptor Alberto Giacometti exemplified extreme version of this compulsive revision. He would work sculptures to near-completion, then destroy them and start over. The struggle toward completion was his actual subject, making traditional finishing problematic.

For such artists, completion might mean accepting that their process involves perpetual dissatisfaction. The work is finished not when it satisfies them but when external factors (deadline, exhibition) or internal exhaustion force stopping.

What Makes Something Feel Complete

Across different approaches to finishing, certain qualities consistently mark work that feels complete rather than merely stopped or abandoned.

Internal Logic and Inevitability

Complete work often achieves sense that it couldn't be otherwise. Each element seems necessary, related to other elements in ways that feel inevitable rather than arbitrary. Changing anything would upset this internal logic.

This doesn't mean the work was predetermined or couldn't have developed differently. But in its finished state, it feels coherent and self-contained. The relationships between parts create whole that seems to complete itself.

Artists sense this when the work begins resisting further changes. Everything they try either doesn't improve it or actively makes it worse. The piece has found its form and won't be improved through additional intervention.

Resolution of Tensions

Successful work often establishes tensions, contrasts, or problems that eventually find resolution. This doesn't mean eliminating tension but finding balance or structure that makes it productive rather than merely unresolved.

Color relationships that initially felt discordant might resolve into complex harmony. Compositional imbalances might find counterweights. Formal problems posed early in process might be addressed. This sense of questions posed and answered marks completion.

Self-Sufficiency

Complete work often achieves independence from maker. It no longer needs the artist's presence or explanation but exists autonomously, communicating on its own terms.

Artists describe this as the work becoming itself. While in process, it exists partly as potential, as something the artist is shaping toward future state. At completion, it fully inhabits its present, needing nothing more.

This self-sufficiency doesn't mean the work is perfect or couldn't have been different. But it means it's genuinely itself rather than incomplete version of something else.

Necessity Not Arbitrariness

Complete work feels necessary—like it had to be this way. Every mark, color, form seems to belong and contribute. Nothing feels merely decorative, superfluous, or arbitrary.

This quality is hard to define but recognizable to experienced viewers and makers. The work has rigor and internal discipline even when it appears loose or spontaneous. Choices feel considered even if intuitive.

Learning to Finish

The ability to complete work effectively develops over time through accumulated experience, failures, and self-knowledge. What seems mysterious to outsiders becomes skill artists develop.

Building Internal Standards

Young artists often struggle with completion because they haven't yet developed clear internal standards. They don't know what they're aiming for well enough to recognize when they've achieved it.

Through repeated practice, artists develop tacit understanding of what makes work successful by their own standards. They learn to recognize when something works not by matching external criteria but by satisfying their internal sense of rightness.

This doesn't mean their standards stop evolving. But having them provides foundation for judging completion. Without standards, you can't tell whether you're finished or just tired.

Learning from Failures

Most artists accumulate substantial catalogue of work they finished too soon or continued too long. These failures become teaching tools for refining completion judgment.

Looking back at overworked pieces helps identify the point where they were actually done before additional intervention degraded them. Examining undercooked work reveals what would have improved it if they'd continued.

This backward-looking analysis gradually calibrates the forward-looking sense of when to stop. Artists build mental library of what various stages of completion feel like.

Developing Trust

Learning to finish often involves developing trust in intuition and process. Early career anxieties about whether work is good enough, finished enough, resolved enough can paralyze decision-making.

As confidence builds through experience, artists become more willing to trust their judgments about completion. They learn that their sense of when something is done usually proves reliable even when they can't articulate why.

This trust doesn't mean eliminating uncertainty but rather functioning effectively despite it. You can feel uncertain and still decide the work is finished based on accumulated evidence that your uncertain feelings at this stage usually correlate with actual completion.

Creating Completion Rituals

Many artists develop personal rituals or habits that support completion. These might involve stepping back for certain duration, photographing the work from various angles, or seeking specific feedback before declaring it done.

These rituals serve psychological function of marking transition from making to finished. They create space between active working and final judgment, allowing fresh perspective.

What Viewers Miss About Completion

Understanding how artists navigate finishing changes how we see completed work. Several implications matter for thoughtful viewing.

Hidden Alternatives

Every finished work represents path taken and numerous paths rejected. The artist made countless decisions about what to include, emphasize, minimize, or eliminate. Each choice closed off alternatives.

Recognizing this helps appreciate that what we see isn't inevitable outcome but specific set of choices from vast possibility space. The work could have been quite different while still being successful.

Evidence of Process

Many works retain visible evidence of the process toward completion. Layers showing through, pentimenti in paintings, marks of revision or adjustment—these traces reveal the journey rather than presenting only final destination.

Attending to these traces helps us see work not as static object but as record of someone's sustained engagement and decision-making. The completion doesn't erase the process but incorporates it.

The Provisional Nature

All completion is somewhat provisional. Artists often remain aware that they could potentially revise, that they might see problems later, that future perspective might reveal limitations invisible now.

This provisionality doesn't diminish the work but humanizes it. Finished doesn't mean perfect or beyond question but rather as resolved as the artist could make it at that moment.

Different Standards Apply

Viewers sometimes wish artists had done more or stopped sooner, not recognizing that different standards of completion apply. What looks unfinished to viewer might be deliberately spare. What seems overworked might reflect necessary process for that artist.

Understanding that completion is partly about artists' internal standards rather than universal criteria helps us meet work on its own terms.

Why Finishing Matters

The question of completion might seem like insider concern, technical issue of interest mainly to makers. But it matters for anyone who cares about art.

How artists navigate finishing reveals their values, their relationship to perfection and imperfection, their willingness to accept uncertainty, their ability to make decisions without absolute certainty. These qualities shape not just whether work gets finished but what kind of work it becomes.

The decision to call something done represents assertion of artistic authority. The artist declares "this is what I made" rather than continuing to hedge by treating it as work in progress. This commitment to specificity over endless possibility represents brave act of self-definition.

For viewers, recognizing the complexity of finishing helps us appreciate the judgment and courage involved in releasing work. Every finished piece represents artist's willingness to stop, to accept this version rather than the potentially better version more revision might produce.

It also reminds us that the art we encounter emerged from process involving countless small decisions, accumulated over time, each bringing the work closer to its final form. The finished state wasn't inevitable but achieved through sustained attention and continuous judgment.

Most importantly, understanding how artists know work is finished reveals that this knowledge isn't mystical or automatic but hard-won through experience, failure, and accumulated wisdom about their own practice. It's skill developed over time rather than gift granted once and for all.

The next time you encounter artwork and wonder whether the artist could or should have done more or different, remember: they almost certainly wondered the same thing. The work exists as it does because at some point, through intuition, system, deadline, or acceptance, they decided it was finished. Understanding how difficult and consequential that decision can be deepens appreciation for both the work and the courage it took to call it done.